User:Robbiemuffin/A Linguistic Presentation of English Grammar Graphics

(At first) this is a grammar of action-sentences. Later, it may incorporate the smaller subset of phrase-sentences (as per titles).

(In the definition of a word, or specifically for the use of a verb, or for phraseal/sentence structure), only the following distinctions will be considered:

- Analytic

- Relative Position – phrasal nearness / injection

- Isolate Concatenation — including auxilliaries

- Affix

- Inflection — excluding agglutination of lexemes

- Agglutination – excluding inflection with morphemes

And any non-trivial combination thereof. For clarity, non-trivial requires an example:

- English has a trivial future-in-the-past tense. «I told you earlier that he will cook dinner for you!» (But you've arrived home with fast food.) It is trivial because, if we were to try to construct the same tense using combinations of simpler tenses in standard english manner, it would either be exactly equivilant to this construct (for example a continuous one: «I told you earlier that he is going to cook dinner for you!»), or it would be equivilant to this tense and simultaneously to a different one («I told you that he would cook dinner for you!»), or it would not be correct (ie, it is possible to poetically invent such a non-trivial tense).

In contrast, Romanian and Bulgarian are langauges that actually have a future-in-the-past tense: Even though one of the simpler tenses is made with an auxilliary, if you construct a future-in-the-past phrase in Bulgarian using trivial combinations (such as above with future and past tenses), the result is still inflected differently.

Lexical Category[edit]

All words are either verbs, nouns, adverbs, adjectives, or narratival words (conjunctions, anticonjunctions, interjections). No category requires demarkation, but it is sometimes common. When words are marked for category, they are affixed:

| Part of speech | Affix |

|---|---|

| Noun | |

| Verb | none in infinitive form |

| Noun Adjunct | LEMMA -ful |

| Verb Adjunct | LEMMA -ly |

| Referent | |

| Narratival |

A generalization which is true for all languages is that words, phrases (incomplete sentences), clauses (complete subsections of a sentence), and full sentences (and so on, even paragraphs, lists, etc), can stand-in for a lexical category. A single word may legitimately have multiple lexical categories. “Set” is a verb, as in To Place At A Specific Position, but it is also a noun, as in A Group.

You might be tempted to think the same thing of “blue”, but that is different. It's two uses as an noun-adjunct are as a Color, and a stand-in equivalence (a stand-in from one type of thing to the same, where it originally was slang) for “sad”. It's use as a noun is really a stand in (excepting domain-specific usage such as biology): in «The sailor was dressed all in blue.», blue is the adjective of all the things she wears, so blue stands in for those objects. Some verbs have zero-valence, and this, usual, type of stand-in can be seen as a zero-valence in a different context.

“Blue” as a noun (from the above) is different from this definition of “set” (noun): The Way in Which Something Is Set, as in «the shape and set of the eyes». Here “set” cannot simply be standing-in for a noun, because it refers to the aesthetic result or manner in which the verb-use would have produced. If one checks a stand-in by drawing a line: Instead of drawing a line directly between nouns and verbs, this sort of stand-in would have to visit verb adjucts between them.

Just to be clear, consider one more verb-as-a-noun stand-in: «On weekends I go for a run.» Here the verb “run” is obviously masquerading as a noun. There is no adjectival in-between state, it is a pure stand-in. (Obviously, in this scheme every verb's usage in the bare infinitive is a stand-in usage for a noun.) Even though the derrivative process is similar to that of “set” in «the determined set of the upper torso» (as above), the complex nature of the “set” example always uses an in-between adjectival state, and so it is properly a different definition of the word.

However, any one sense of a word will principly only have one lexical category. Likewise with phrases, as in «the great white hope», which are always incomplete. (In this case that phrase is a noun-phrase, but it could perhaps stand in for something else.)

Clauses (which are complete sentences in their own right but are in practice only a part of a sentence) and larger word-clusters will all typically only stand-in as nouns-for-<something>.

Noun[edit]

Nouns are commonly described as any person, place, thing (physical or areal). In a sense, english nouns are very wide; english has many forms of non-finite verbs: gerunds, such as «seeing», and infinitives such as «to see».

The phrase «Seeing is believing» is equivalent in meaning with «to see is to believe».

Verb[edit]

Verbs are action or event words, or in non-finite form are really basically nouns. English has a normal compliment of verbs with few conjugations.

- Verb as an action – «I wrote a long entry in my diary today.»

- Verb as an event – «He died last Tuesday.»

- Verb as an auxilliary – «I am writing.»

- Verb in nonfinite form can stand-in for a noun – «I love to write.»

English is evolutionarily mid-way between being a fusional language, tending towards/becoming a analytic, isolating language. As such, there is an extensive and verigated use of copula.

English supports full valency, with addition of dummy pronouns for null-subject sentences:

| Valency | Form | Example | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Null-subject | Use of dummy pronoun it | «It rains.» |

| 1 | Intransative | «I run.» | |

| 2 | Transative | «She reads a book.» | |

| 3 | Ditransative | «He gave her peace.» |

Noun Adjunct[edit]

Noun adjuncts are adjectives.

Adjectives adjust nouns in their roles as objects or subjects of sentences. They may also mark event-typed noun phrases (in He ran fast and hard., he wasn't fast and hard, but rather how he ran was fast and hard). Adjectives may be used in any of these ways:

- Attributive — Adjectives demark attributes of nouns, usually by prepending the noun — «The good son.»

- Predicative — Adjectives may demark attributes of nouns by tunneling through a verb — «That made me happy.»

- Absolute — Adjectives may demark attributes of nouns, while structurally isolated from them — «The protestors, relieved that there was no violence, interrupted their march to rest.»

There is also a substantive use of adjectives as nouns, where the adjective or adjectival phrase is a stand in for a noun, such as «The meek shall inherit the earth.» Here, “the meek” stands in for “all who are meek”.

Syntax[edit]

Adjectives may affect their nouns thusly:

- Adjectives prepend their nouns — «The good son.»

- Adjectives may tunnel through a verb — «The dog grew angry.»

- Adjectives may work alone or serially — «When shopping for sports cars, always remember the adage: the small, red coupe gets the tickets.»

When more than one adjectives are used, there are guidelines of clustering (these are not hard and fast rules, just guidelines):

- Each adjective belongs to a primative class. For example, “red” and “green” are both of class Color.

- If there are two or more classes, adjectives must clump together in groups, and generally progress towards the larger groups — «the tall, fast, brown and white stallion.»

- Classes that are otherwise equally represented have a general order: Physicality precedes Temporality preceeds Color.

- If there are two adjectives of the same class, “and” is placed between them — «He is the fat and tall one.»

- If there are more than two adjectives in the same class, they are comma-separated except the last (Which uses an “and”) — «The quick fat and tall one.»

Adjectives are almost always demarked by a suffix (this is generally a trace element of the host language of the loan words, as english is basically just a creole + time).

Common suffixes (derrived from http://www.michigan-proficiency-exams.com/suffix-list.html and http://www.class.uidaho.edu/luschnig/EWO/4.htm)

| suffix | meaning | usage |

|---|---|---|

| -ful | full of | dreadful |

| -able, -ible | capable of | portable, legible |

| -al, -nal | relating to, characteristic of | maniacal, maternal |

| -il, -ile | like, capable of | civil, fissile |

| -ous | full of | nauseous |

| -ive | like | qualitative |

| -ary, -ar | like, connected with | honorary, molar |

| -fic, -ic | event characteristic | terrific, sonic |

| -ate | like, in the class of | literate |

| -ac, -ic | like, relating to/from the/connected with | cardiac, aquatic |

| -acious, -icious | full of | spacious, avaricious |

| -ose | full of | verbose |

| -an, -ane, -ine | like, in the class of | urban, urbane, feline |

| -ant, -ent | full of | suppliant, eloquent |

| -oid | resembling, in the class of | ovoid |

| -aceous, -iceous, -eal | relating to | miscellaneous, sebaceous., arboreal |

| -escent | becoming | evanescent |

| -iferous | bearing | pestiferous |

| -ly | in the manner of (psuedo-adverbial) | friendly |

Comparison[edit]

Adjectives may be compared in a quasi-quantitative fashion. Some words requre the use of an auxilliary for this purpose. Others can do so using suffices:

| degree | quantity | suffix |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | equivocal | |

| 1 | comparative | -er |

| 2 | superlative | -est |

Phrases and nouns can “stand in” for (act in place of) adjectives.

Verb Adjuncts[edit]

Verb adjuncts are the typical form of adverbs.

Adverbs adjust verbs. They may also adjust adjectives, and adverbs. (in He ran extremely fast., the running wasn't extreme, but rather it's fastness). Adjectives characterize an event, or an action, and as such they tend to be presented as answering a qualitiative question: how? when? were? why? (comparatively) how?

Some treatments of adverbs handled them as a catch-all, under the notion that any class or specific word that serves different purposes is necessarily categorically different. I would like to disabse the reader of any such concept. If you separate out, form the classical adverbs, all those that distinguish by time and place, the remainder follows these rules. The time and place adverbs may be treated like determiners (which specify definiteness or indefiniteness along poles of time/place). However, this is of no great importance; even continuing to count words such as "always" or "here" as adverbs, only the rules of placement need change.

Syntax[edit]

Adverbs typically go before that which they compare:

- «That is a surprisingly dark rabbit.»

- «He joyously runs along.»

In the particular case where the adverb modifies the verb, it may for emphasis, modify the position to the beginning or end of the phrase, clause, or sentence:

- «He carefully drove the car.»

- «He drove the car carefully.»

- «Carefully, he drove the car.»

The equivalent form of positional change for an adverb modifying something other than a noun changes the adverb to instead modify the phrase or sentence (with a corresponding change in meaning):

- «That is a surprisingly dark rabbit.»

- «Surprisingly, that is a dark rabbit.»

- «That is a dark rabbit, surprisingly.»

Common suffixes are: (from http://www.iee.et.tu-dresden.de/~wernerr/grammar/suffixes_eng.html)

| suffix | quanlity | example |

|---|---|---|

| -ly | in the manner of | awkwardly |

| -wards. -ways, -wise | in the direction of | backwards, sideways, clockwise |

Comparison[edit]

Adverbs are only compared paraphrastically.

Adverbs can be stood-in for (replaced by) adverbial phrases and clauses.

Referent[edit]

Referents are (most) determiners and the atypical adverbs.

In english, a determiner may:

- Stand in place of a noun, acting directly as a pronoun

- One must speak humbly about oneself.

- This is so difficult to understand!

- Stand in place of an adjective

- Not just some, but many ...

- No few people have read Cooper.

Otherwise it will act in its more natural form as a reference mark for a noun (or noun phrase). This demarkation in english is either definite (such as “the”) or indefinite (such as “a”), which acts as a count or specificity characterization rather like adjectives. Because of this dual role, and its common fill-in usage as a noun or an adjective, it is easy to think of determiners in english as strictly in between nouns and adjectives.

- The lady is a tramp.

- Some girls get all the luck.

- Which book is that?

- That book is my book.

- I only had two drinks.

In addition to determiners, there is a second class of referent. The second class is of adverbs which, when not standing in for nouns, specifically adjust phrases, clauses, or sentences with place or time relations (either definiteness or comparison), such as: there, here, today, tomorrow, always, often, etc.

|

|

| |

Usually these words adjoin their modifees by some form of concatenation: whether at the beginning or the end of the phrase, etc, that they modify. But some, such as always, often will interpolate into their phrase, sentence, etc, right before the verb of the clause they modify. For example:

- «He is always late for work.»

- «Always, he is late for work!»

Note that changing the adjunction from interpolation to concatenation is legitimate, just not common.

One might divide (as in the images above) this second class into 3 types, two of which adjust time, only in different ways, and the other is for position (as in space). You may look at determiners as a 4th type, a sister to the positional adverbs. However, this time it is an abstract positional.

The words of this second category are traditionally considered adverbs, but they basically provide the same role as count or definiteness determiners, only in different domains. Adverbs which are made from adjectives, in general, and adverbs which adjust verbs, are (still) considered verb adjuncts. It is only Time, Place, Frequency, and State -classed, matter-of-degree adverbs which have been included in this category.

Narratival[edit]

|

|

«Therefore», «lest», and others which guide the interpretation (in terms of meaning, time, or pace) of the sentence, are grouped together here as Narrativals. When misused, like at the start of a sentence, conjunctives such as «and», «or», and «but» will stand in for narrativals. Their equivalents: «furthermore», «optionally», and «however» are properly considered narrativals.

Typically the narrativals that are not proper conjunctives are considered adverbs.

Person[edit]

* see English_personal_pronouns

Grammatical person, in linguistics, is deictic reference to the participant role of a referent, such as the speaker, the addressee, and others. Grammatical person typically defines a language's set of personal pronouns. It also frequently affects verbs, sometimes nouns, and possessive relationships as well.

Here is a table of grammatical person related to both pronouns and verb conjugations.

| subjective | objective | reflexive | possesive | possessive determiner |

regular inflection | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| first person | singular | I | me | myself | mine | my | ||

| plural | we | us | ourselves ourself |

ours | our | |||

| second person | singular | you | yourself | yours | your | |||

| plural | yourselves | |||||||

| third person | singular | masculine | he | him | himself | his | his | -s |

| feminine | she | her | herself | hers | her | |||

| neuter generic |

it they |

it them |

itself themself |

its theirs |

its their |

-s none | ||

| plural | they | them | themselves | theirs | their | |||

* italic words are nonstandard.

Inflection based on person is always replaced by other verb affixes.

first person[edit]

| subjective | objective | reflexive | possesive | possessive determiner |

regular inflection | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| singular | I | me | myself | mine | my | |

| plural | we | us | ourselves ourself |

ours | our |

- subjective

- «I run in the marathon every year.»

- «We run in the marathon every year.»

- regular inflection

- «I run in the marathon every year.»

- «We run in the marathon every year.»

- objective

- Direct Object (As in a photo) «This is me, running the marathon.»

- Direct Object (As in a photo) «This is us, running the marathon.»

- Indirect Object «You gave me a run for my money.»

- Indirect Object «You gave us a run for our money.»

- reflexive

- «I cannot run the marathon by myself.»

- «We cannot run the marathon by 'ourselves.»

- possessive

- «The marathon is mine!»

- «The marathon is 'ours!»

- possessive determiner

- «My last marathon was almost too difficult to finish.»

- «Our last marathon was almost too difficult to finish.»

second person[edit]

|

|

The personal “you” is in the second person. It refers to the addressee. “You” is used in both the singular and plural. |

| subjective | objective | reflexive | possesive | possessive determiner |

regular inflection | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| singular | you | you | yourself | yours | your | |

| plural | you | you | yourselves | yours | your |

- subjective

- «You run in the marathon every year.»

- regular inflection

- «You run in the marathon every year.»

- objective

- Direct Object (As in a photo) «This is you, running the marathon?»

- Indirect Object «I gave you a run for your money.»

- reflexive

- «You cannot run the marathon by yourself.»

- possessive

- «The marathon is yours!»

- possessive determiner

- «Your last marathon was almost too difficult to finish.»

third person[edit]

|

|

“He”, “she”, “it”, and “they” are in the third person. Any person, place, or thing other than the speaker and the addressed is referred to in the third person. Informally "they" is often used to remain gender-neutral, even when speaking about a single individual.

| subjective | objective | reflexive | possesive | possessive determiner |

regular inflection | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| singular | masculine | he | him | himself | his | his | -s |

| feminine | she | her | herself | hers | her | -s | |

| neuter generic |

it they |

it them |

itself themself |

its theirs |

its their |

-s none | |

| plural | they | them | themselves | theirs | their | ||

- subjective

- «He runs in the marathon every year.»

- «She runs in the marathon every year.»

- (About the marathon) «It comes every year.»

- «They run in the marathon every year.»

- regular inflection

- «He runs in the marathon every year.»

- «She runs in the marathon every year.»

- (About the marathon) «It comes every year.»

- «They run in the marathon every year.»

- objective

- Direct Object (As in a photo) «This is him, running the marathon.»

- Direct Object (As in a photo) «This is her, running the marathon.»

- Direct Object (About the marathon & as in a photo) «This is it, the one we run every year.»

- Direct Object (As in a photo) «This is them, running the marathon.»

- Indirect Object «You gave him a run for his money.»

- Indirect Object «You gave her a run for her money.»

- Direct Object (About the marathon & as in a photo) «This is the marathon; we gave itour best shot.»

- Indirect Object «You gave them a run for his money.»

- reflexive

- «He cannot run the marathon by himself.»

- «She cannot run the marathon by herself.»

- (About a vendor stand at the marathon) «You must man the stand, it will not run itself.»

- «They cannot run the marathon by 'themselves.»

- possessive

- «The marathon is his!»

- «The marathon is hers!»

- «The marathon is 'theirs!»

- possessive determiner

- «His last marathon was almost too difficult to finish.»

- «Her last marathon was almost too difficult to finish.»

- (About a previously popular marathon) «Its last run was in 2005.»

- «Their last marathon was almost too difficult to finish.»

indefinite[edit]

The indefinite in english is defective, and so is not included. Nonetheless, it is an oft-used part of speech with a nearly complete set of uses, in fact it is almost overly robust. If you would like to read up on it, please see User:Robbiemuffin/indefinite person. However it should be considered supplimental to an english-centric presentation of the english langauge, and not compatible directly with a coverage like that herein.

Grammatical Use of Verbs[edit]

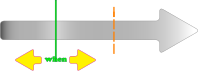

(key)[edit] | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

Analytics[edit]

Analytic verb change uses words relative to the verb to change the verb. They break down to two main categories, those that string words together in a specific way, called isolating concatenation here, and those that place words relative to other words (for example, such as relative tenses in exotic languages, but also in terms of clausal constructions with many of the modal verbs in english).

Very nearly all languages derrive meaning not only from the individual words but their placement. In español, it does not matter if you say ¿tú me entiendes? or ¿tú entiendes me?, the one is different from the other only in terms of the emphasis the speaker wishes to present. Analytic usage stand in contrast to that form of meaning assignment: it is formalized, the additional meaning is prescriptive in application.

Relative Concatenation[edit]

Relative concatenation is where, under certain conditions, the modifying particle can drift independently of the modified verb.

see Relative Concatentation for fuller coverage of relative concatentation in english and modal verbs.

The Conditional Mood effects the if clause of an uninstantiated cause-and-effect statement with such an if clause. It fairly strictly requires more than one clause. («Someone who likes red and hates yellow would probably prefer strawberries to bananas» does not explicitly use the word “if”; still it is conditional.) It is a specific instance of the subjunctive.

The Subjunctive Mood effects the principle verb in any statement about possiblity, probability, expectation, etc. This includes uninstaniated cause-and-effect statements. («I hope you like pudding.» is subjunctive even though there is no cause-and-effect statement.)

The previous two moods are serial constructors, covered in the next section.

The Normative Mood expresses wishes, hopes, desires, that which is poper, expected, ideal, and the inverse of those things. It adds emphasis (like the intensive tenses in some treatments, etc), and is used for assertion.

The Imperative Mood expresses direct commands or requests. It is also used to signal a prohibition, permission, cohoration, or any other kind of exhortation.

Isolating Concatenation[edit]

In isolating, analytic languages this is often called serial construction or just concatenation. It is a characteristic of any isolating language, whereby many words are presented in almost strict adjecency to form a logically different concept. It is most often done with nouns: english has a true wealth of phrases that are distinct in virtually all ways from their normal, isolated meaning. Here we cover the same effect specific only to verbs.

* The “will” form is referred to as the Lemmafut, while the so-called “going to” form is usually named explicitly.

** Note that the perfect aspect can only rarely sit bare in a sentence. Normally it requires an auxilliary verb.

| non-finites | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| infinitive quality bare infinitive quality * |

to Lemma ([less* to] Lemma) |

To be gentle at massage, rub but do not use pressure. I play the violin. | |

* The (de facto) form referring to a verb out of context is the isolate concatenation form (such as «to run»), but the standard form of the verb (as used in linguistics), is the unnumbered bare infinitive. Herein they are made explcit:

- Lemmainf the infinitive

- Lemma the standard form

The Conditional Mood effects the if clause of an uninstantiated cause-and-effect statement with such an if clause. It fairly strictly requires more than one clause. («Someone who likes red and hates yellow would probably prefer strawberries to bananas» does not explicitly use the word “if”; still it is conditional.) It is a specific instance of the subjunctive.

The Subjunctive Mood effects the principle verb in any statement about possiblity, probability, expectation, etc. This includes uninstaniated cause-and-effect statements. («I hope you like pudding.» is subjunctive even though there is no cause-and-effect statement.)

Affixes[edit]

Inflection[edit]

Inflection is the usual form of latinate languages to express verb qualities. English is notably poor in terms of verb inflection.

| zero inflection | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| nonpast tense * | (Lemma) |  It dies. | |

* Note that the default form of the nonpast tense is the present tense.

| suffix | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| past tense * | Lemma -ed |  It died. | |

| Lemma -en ** | The river was swum by necessity. | ||

| progressive aspect | Lemma -ing |  I am going. | |

* Note that combining tense and quality is legitimate (although the infinitive is the standard form so no change occurs). Nonetheless, the past non-finite form, for example «I wrote» is less common than the more colloquial auxilliary form of the non-finite: «used to write».

** The participle form of a verb cannot stand bare, but is used to help perfective or passive senses of the verb.

Agglutination[edit]

| prefixive agglutination | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| causation quality | (be+Lemmaadjective) |  Wishing for sleep, the lights were bedimmed. | |