User:Nokia 1280/Note

This is Nokia 1280's notes site. Do not do anything.

Government[edit]

Central government[edit]

The new government of Lê Lợi was modeled on the Ming dynasty system. Previous Trần dynasty had only Three ministries: Lại, Lễ, Dân, now under Lê Dynasty it was expanded to Six Ministries: Lại bộ; Lễ bộ; Hộ bộ; Binh bộ; Hình bộ; Công bộ.

By level-administrative, population[edit]

The administrative census An Nam quốc đồ (安南國圖) in 24 April, 1490 showed Đại Việt had 13 thừa tuyên (provinces), 52 phủ (urbanized cities, towns), 178 huyện (districts), 50 châu (mountain districts), 20 hương , 36 phường (Đông Kinh's urbanite districts), 6851 xã (communes), 322 thôn (rural villages), 637 trang (mountain villages). Total population was various estimated about 8,000,000–10,000,000 people.[1] In contrast to the overpopulation Red river delta, Thuan Hoa and Quang Nam region were still less dense. Vietnamese people had begun settling in the conquered Cham land at least since the 1400s. After Nguyễn Hoàng appointed the governor of southern provinces in 1572, million people migrated to the south, resulted in the degenerated Champa kingdom and Cambodia's land were being taken by the Vietnamese authorities.

Law[edit]

In 1429, Lê Lợi introduced new Thuận Thiên code which mostly based on the Tang code, with severely charges for illegal gambling, bribery and corruption.[2][3] To sought a consolidation of a powerful central government, in 1483 Emperor Thánh Tông introduces a new code name Hồng Đức Code which was heavily influenced from the Ming Dynasty Laws and Neo-Confucianism thought, restricting the free of expressing in society, banning illegal marriages, banning divorce, limiting women right.[4][5][6]

=================================================================================================================[edit]

Society, culture and science[edit]

Clothing and society[edit]

After ending the Fourth Chinese domination of Vietnam, people of Đại Việt started to rebuild the country. Because the Ming invaders had destroyed almost documents from the previous dynasties of Vietnam, the government had to reconstruct, reused old clothes from previous dynasties, mostly Trần dynasty. From 1428 to 1437, Vietnamese bureaucrats wore red and green round-neck viền lĩnh, Toàn Hoa hat, while the emperor dressed yellow viền lĩnh and wore on his head Tongtianguan or Putou (襆頭) which were some similar to the Tang empire's clothing. In 1435 Lê Lợi had appointed the high-rank mandarin Nguyễn Trãi to find the new costume adoption, but Nguyễn Trãi had failed on a debating with another mandarin name Lương Đặng, who strongly suggests adopting Ming clothing.[7] Since November 1437, the new dress regulation for emperor and whole bureaucracy system was adopted, which resembled from the Ming dynasty, included for every commune, district to province quan in the country. High-rank mandarins from 3rd to 1st wore red robes, medium-rank mandarin from 5th to 4th wore green robes, and all lowers wore blue robes, and all Mandarins wore mũ Ô Sa (a Vietnamese longer variant Wushamao 烏紗帽).[8] During the first period, Lê emperors wore the mũ Xung Thiên (Yishanguan 翼善冠), which was sent from Ming Dynasty, for examples, in October 1442, Lê Nhân Tông received mũ Xung Thiên from Emperor Yingzong of Ming.[9] During this period, cross-collared robe called áo giao lĩnh was popular among civilians.[10][11] Before 1744, people of both Đàng Ngoài (the north) and Đàng Trong (the south) wore giao lãnh y with thường (a kind of long skirt). Both male and female had loose long hair. In 1744, Lord Nguyễn Phúc Khoát of Đàng Trong (Huế) decreed that both men and women at his court wear trousers and a gown with buttons down the front. That the Nguyen Lord introduced early variant of áo dài (áo ngũ thân). The members of the Đàng Trong court (southern court) were thus distinguished from the courtiers of the Trịnh Lords in Đàng Ngoài (Hanoi), who wore giao lĩnh with long skirts. The partition between two families over the country too long so caused the some major differences in Vietnamese dialect and culture between Northern and Southern Vietnamese.

The seventeenth century was also a period in which European missionaries and merchants became a serious factor in Vietnamese court life and politics. Some early intermarriages between Vietnamese and Westerners had been occurred sixteenth century. There were the beginning of Although both had arrived by the early sixteenth century, neither foreign merchants nor missionaries had much impact on Vietnam before the seventeenth century. The Portuguese, Dutch, English, and French had all established trading posts and factories in Đông Kinh and Phổ Hiền by 1680. Fighting among the Europeans and tax pressures from the Vietnamese court made the enterprises later unprofitable, however, and all of the foreign trading posts were closed by 1800.

The class tension between the main population of landless peasants, poor workers to landlords, factory owners, bureaucrats and the noble class had been climbed to the peak in mid 1700s, with many peasant rebellions, protests, uprising through out the country.[12] However they didn't had well and totally effective until the Tây Sơn rebellion which ultimately successful overthrew two powerful Trinh-Nguyen families and the Imperial court in 1789. The 17-vol historical novel Hoàng Lê nhất thống chí (皇黎一統志) written from 1770 to 1802 had full discovered of this chaotic period in the Vietnamese history.[13]

Entry of Christianity in Vietnam[edit]

European missionaries had occasionally visited Vietnam for short periods of time, with some impacts, beginning in the early sixteenth century. Khâm định Việt sử Thông giám cương mục recorded the first Christian missionary name Inácio in the first year of Nguyên Hoà (1533) in Nam Định.[14] From 1580 to 1586, two Portuguese and French missionaries Luis de Fonseca and Grégoire de la Motte worked in Quảng Nam and Quy Nhơn region under lord Nguyễn Hoàng. After the Lê–Mạc War ended and peace was restored in 1593, more missionaries from Spain, Portugal France, Italy and Poland came to Vietname to make efforts for Christianity conversion. The best known of the early missionaries was Alexandre de Rhodes, a French Jesuit who was sent to Hanoi in 1627, where he quickly learned the language and began preaching in Vietnamese. Initially, Rhodes was well received by the Trinh court, and he reportedly baptized more than 6,000 converts; however, his success probably led to his expulsion in 1630. He is credited with perfecting a romanized system of writing the Vietnamese language (quốc ngữ), which was probably developed as the joint effort of several missionaries, including Rhodes. He wrote the first catechism in Vietnamese and published a Vietnamese-Latin-Portuguese dictionary; these works were the first books printed in quốc-ngữ. Quốc-ngữ was used initially only by missionaries; hán tự or chữ nôm continued to be used by the court and the bureaucracy. The French later supported the use of quốc ngữ, which, because of its simplicity, led to a high degree of literacy and a flourishing of Vietnamese literature. After being expelled from Vietnam, Rhodes spent the next thirty years seeking support for his missionary work from the Vatican and the French Roman Catholic hierarchy as well as making several more trips to Vietnam. However, since 1910, Latinized Quốc ngữ was adopted by the French governor as the main writing system of Vietnam[15], while hán tự and nôm tự fell into declinine. Vietnamese Christianity developed and became stronger, thanked to efforts of Western missionaries, till the end of XVII century, there were about 100,000 followers in North Vietnam and 40,000 in South Vietnam, but still was a minority part compared to the country.

Science and Philosophy[edit]

The Lê period was the continuously flourish era of Vietnamese scientific and Confucianism scholaric. Nguyễn Trãi was a 15th-century Lê official, author of geography book Dư địa chí, also was a Neo-Confucianist scholar. Lê Quý Đôn was a poet, encyclopedist, and government official, author of the geography book Phủ biên tạp lục. Hải Thượng Lãn Ông was a famous Vietnamese doctor and pharmacist with his full collection 28-volumes Hải Thượng y tông tâm lĩnh about traditional Vietnamese medicine. Gunpowder usage had been appeared in Vietnam very long time, some said it spread to Annam during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period, or being sooner during the Tang dynasty.[16] However, until 1380, the Vietnamese had begun building their own bronze guns, which were transferred from Ming Chinese technologies.[17] Matchlock firearms technology also spread from India and Portugal to Đại Việt in 1516, and was adopted and produced by the Lê army by 1530s.[18]

Literature and arts[edit]

The Lê Dynasty also saw the very flourish era of Vietnamese literature, especially written in chữ nôm, a Vietnamese variant of Chinese characters but in native Vietnamese words. Many types of entertainment and artistic sports, poetry, painting, stories, books, hát tuồng, chèo, cải lương, ca trù, ... developed to the peak and official annually held in theaters. Many writers that were author of many popular stories and poets in Hán tự or chữ nôm; for examples, Nguyễn Du with his infamous The Tale of Kiều, Đoàn Thị Điểm with Chinh phụ ngâm, Nguyễn Gia Thiều with Cung oán ngâm khúc,...

Emperor Lê Thánh Tông himself was a great author of many books and collections of his own poems and others in classic Chinese, some records:

- Thiên Nam dư hạ tập (天南餘暇集)

- Quỳnh Uyển cửu ca (瓊苑九歌) - collection of 9 musical essays

- Minh lương cẩm tú (明良錦繡) - 18 poems about beauties of beaches in Central Vietnam

- Văn minh cổ súy (文明鼓吹) - collection of poems about ancestors

- Chinh Tây kỷ hành (征西紀行) - collection of 30 chronicles about Champa Kingdom

- Cổ Tâm bách vịnh (古心百詠) - a collection of Ming Chinese poet Tianzi Yi

- Châu cơ thắng thưởng (珠璣勝賞) - collection of 20 poems about temples in the country

- Anh hoa hiếu trị (英華孝治)

- Cổ kim cung từ thi tập (古今宮詞詩集)

- Xuân vân thi tập (春雲詩集) - Poems about the Lunar New Year.

From XVI century in northern Vietnam, around Hanoi born new woodblock painting and silk painting traditions, for examples the Đông Hồ and Hàng Trống. Another form of Vietnamese paintings are Taoist painting, Buddhist painting and New Year painting (tranh Tết). The art forms of that time prospered and produced items of great artistic value, despite the upheavals and wars. Woodcarving was especially highly developed and produced items that were used for daily use or worship. The Vietnamese art later was also influenced by Japanese and Western arts. Many of these items can be seen in the National Museum in Hanoi.

-

Woodcut paintings "Thánh Cung vạn tuế" ("Long live his Imperial Majesty") from the 18th-century Nghệ An.

-

Wooden Arhats, 1646-1647

-

Statue of Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva, crimson and gilded wood, Revival Lê dynasty, autumn of Bính Thân year (1656), from Bút Tháp pagoda in Bắc Ninh Province.

-

Wooden art pieces of the seventeenth century.

-

Nghe (mythological beast) figurines, crimson and gilded wood, eighteenth century.

-

Lion decorate in seventeenth century.

-

Dragon of the Later Lê dynasty.

-

Buddhanandi statue of the Le dynasty.

-

Ceramic Lion bush , sixteenth century.

-

Bronze bell in Hoi An, 1677.

==========================================================================================================================[edit]

Economic development[edit]

Early period (1428–1567)[edit]

Since Annam gained fully independent from China in 939, the capital Đại La of the kingdom continued being a economy and trading center of Vietnam, with small amounts of foreigner merchants came from Song China, Champa, Dali kingdom, Srivijaya, Western Xia and Đại Thực (Arab).[19][20]. When the Mongol-ruled Yuan Dynasty set a blockade to Dai Viet and Champa kingdom from 1282 to 1330 that cut of the Maritime trade route from Vietnam to Southeast Asia and West Asia that severely weakened the kingdom's economy. In 1371, Zhu Yuanzhang of Ming China imposed the Sea Ban in China that gave opportunities for surrounding kingdoms, including Vietnam. However in 1406 the Ming dynasty invaded Vietnam, overthrew the short-live Hồ dynasty (1400–1407) and set up the occupied Fourth Chinese domination of Vietnam. The Ming army looted, destroyed and burned many valuable books, treasures back to China, attempt to total restriction on local population's monetary hands and to assimilate Vietnamese into Ming Empire, that causing severely damages on Vietnamese economy.[21]

After Lê Lợi led the Lam Sơn rebellion drove out the Chinese in 1427, he sought to restore the agriculture by made a Land reform in April 1428, sized lands from Ming collaborators and the wealthy noblemen to distribute land to peasants and the growing population. Approximately 250,000 reserve soldiers were back to their home to help restore the farming crops.[22] Lê Lợi also replaced the previous Hồ's paper banknotes Hội Sao Thông Bảo by the new currency Thuận Thiên thông bảo (Yuantian Tongbao), which 50 bronze đồngs equal 1 bronze-silver tiền. Each đồng weights 2,67 gram. Supported by the scholar-bureaucrats, he accepted the Confucian viewpoint that merchants were solely parasitic, but still encouraged the handicraft industry, ceramics manufacturing, metal mining and silk trade however he put them under the state control to prevent Chinese infiltrators. Because the restriction on trading, Đông Kinh and Vân Đồn were only two places where foreigners could exchange for goods. Lê Vietnamese's blue and white underglaze-cobalt celadon ceramics made from Chu Đậu were the most finest and gained dominant ceramics in Asian market at that time. They were exported to Southeast Asia, China and West Asia. The Ottomans called them "Annam wares". Estimated, about up to 10% of ceramics exported to Europe during 1400-1567 were Vietnamese products.[23] By the year of 1460, Vietnam's economy had been fully recovered and gained triple by size of crops and reverse golds in national storage.[24] During the conquest of Champa and occupation of Laos, Emperor Lê Thánh Tông's campaign took 1,000 liangs of gold each day[25], looted gold treasures and new conquered lands improved the court's reserve monetary. Vietnam enjoyed a period of political stability and prosper society.

However, after king Thái Trinh Lê Thuần died in 1505, the country's economy began shrinking down because following kings like Lê Uy Mục, Lê Tương Dực who were incompetent and only interested in eating, entertaining, sexual than doing as rulers of the country caused disruptive peasant and military rebellions through out the country. There was series of severe famines in Hải Dương prefecture and Kinh Bắc prefecture (Bắc Ninh, Bắc Giang) occurred in 1517 to 1521 during the reign of Lê Tương Dực.[26] The sixteen-century political crisis caused severe damages to Vietnamese's agriculture and conscription required by incessant military campaigns, compounded by natural disasters, largely contributed to regular crop failures. Number of landless peasant grew quickly, causing a disproportionate surplus of unemployed labours, and the wealthy factory owners, landowners grew in numbers. After Mạc Đăng Dung gained power in 1527, he sought to recover the economy again by employed landless peasants into cities, opening ceramic, silk factories and mining fields. The Mac rulers maintained their economy closely to the Ming China, later in 1572 the Northeast coast of Vietnam was raided by Wakou pirates.[27] After recaptured Dong Kinh in 1592, the Lê-Trịnh court acknowledge the benefits of oversea trading, continue encourages handicraft industrial and opened some international ports like Hoi An, Dong Kinh for the presence of foreign merchants. About 80% of the population were farmers and peasants; they worked on lands mostly were held by địa chủ or the landlords.

Later period (1567–1789)[edit]

The Vietnamese ceramic business had come to the declining and crumble period when in 1567, the Ming Emperor Longqing had lifted China's Haijin (Sea Ban) policy that make Chinese ceramic products be able to flooded and regained dominant in Asia.Template:Sfnp Maritime trade intendancies were reëstablished at Guangzhou and Ningbo in 1599, and Chinese merchants turned Yuegang (modern Haicheng, Fujian) into a thriving port.Template:Sfnp The Vietnamese Imperial court now seeked to product more valuable production, mostly silk, to sold them for the Portuguese merchants from Macao, later mainly sold for the VOC in Batavia and the British companies. This exchanging period with Westerners gave the Vietnamese unique European and West Asian products. The Portuguese also imported to Vietnam new seeds of tomato, potato, corn and pineapple from Americas as well.[28] The VOC ultimately helped the Trinh lords armed his army with new European weapons, military assignment against the Nguyen lords in the south with allied with the Portuguese.[29]

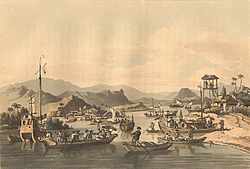

Silk trading was important at that time and Chinese and Japanese traders came to Dong Kinh to buy both high quality silks and raw silks. Besides silk textiles were made by villages, majority of them were produced in state-owned factories in Dong Kinh, which produced for the Royal family, noblemen and foreigners.[27] In 1637, the Dutch successfully established commercial and diplomatic relations with Tonkin and maintained their trading station in the capital of Thăng Long (present-day Hanoi) until 1700. The lucrative Dutch ‘Vietnamese-silk-for-Japanese-silver trade‘ later also attracted the English and the French to Tonkin in 1672 and early 1682 respectively. The British imported Vietnamese silk around 1670s, but not regularly. The city had a Chinatown, factories owned by Dutch, English companies along the Red river.[30] In 1594, the Imperial court allows the Western presence in the capital, encouraged Dutch, Spanish and British to open trading ports. In 1616, the British established a factory in Đông Kinh, but their business were ended in failure due to the pressures from the Lê court, and finally withdrew in 1720.[31] During the 17th and 18th century, Westerners commonly used the name Tonkin (from Đông Kinh) to refer to northern Vietnam, then ruled by the Trịnh lords (while Cochinchina was used to refer to Southern Vietnam, then ruled by the Nguyễn lords, and Annam, from the name of the former Chinese province was used to refer to Vietnam as a whole). Tonkin had been a major industrial factory and trading center in Asia until 1730s.[32] The prosperity of Northern Vietnam during 1600s was described through the urbanization in Tonkin through Western narratives: "...Cachao (Dong Kinh) probably had 200,000 houses. The city size was some larger than some the largest cities in Europe but similar size to other major Asian cities. It lies along the Red river...there are 36 stone-paved major streets, many people from areas to foreigners such as Chinese, Japanese, English held their business companies, factories and stores here...the Emperor has three small but magnificent palaces, mostly built by red wood and terracotta bricks, surrounded by 15-feet height wall, and its main gate never opens expect when the Emperor wants to go outside. The Trinh king (lord) and his families live in Ngũ Long castle, near Tạ Vọng lake, can be seen the highest palace from the Red river..."[33]

In 1612, Joseon army encountered a Vietnamese merchant ship from Tonkin wrecked in Jeju Island carried a lot of treasures and money. The Koreans killed all sailors, looted treasures on board then falsely reported the ship "was a pirate ship".[34]

However, by the last quarter of the 1600s, Tonkin was no longer a profitable trading place. Vietnamese silk no longer reaped a handsome profit in Japan and Vietnamese ceramics proved unmarketable in the insular Southeast Asian markets. In Tonkin, trading conditions also deteriorated rapidly. Subsequently, natural disasters ravaged the economy of the country and a wave of successive famines discouraged local craftsmen from producing goods for export. Worse still, after the protracted civil war with the southern Vietnamese kingdom of Quinam (or Đàng Trong) ended in 1672, the Tonkinese rulers seemed to be more indifferent towards foreign trade as they were no longer in urgent need of a supply of weapons from the Westerners. Bearing in mind their long-term strategy, especially the prospect of opening up trading relations with China, the Dutch still wanted to maintain their Tonkin trade despite its current unprofitable state, perceiving that it would be extremely difficult to re-establish the relationship with Tonkin once they left the country.[27] Despite the Dutch persistence, the relationship between the VOC and Tonkin deteriorated rapidly during the last two decades of the seventeenth century, especially after Chúa (Lord) Trịnh Căn (r. 1682–1709) succeeded to the throne.[27] All European trading ports in North Vietnam were being closed by late 1780s due to the unstable during the Tây Sơn rebellion was spreading north and overthrew the dynasty in 1789.

Expand settling lands in Southern Vietnam to Cambodian land[edit]

The area of Quảng Nam river original was part of Champa kingdoms and was annexed by Đại Việt since 1471. It was opened for foreign merchants trade and reside. In 1535 Portuguese explorer and sea captain António de Faria, coming from Da Nang, tried to establish a major trading centre at the port village of Faifo.[35] Hội An was founded as a trading port by the Nguyễn Lord Nguyễn Hoàng in 1570. The Nguyễn lords were far more interested in commercial activity than the Trịnh lords who ruled the north. As a result, Hội An flourished as a trading port and became the most important trade port on the East Vietnam Sea. Captain William Adams, the English sailor and confidant of Tokugawa Ieyasu, is known to have made one trading mission to Hội An in 1617 on a Red Seal Ship.[36] The early Portuguese Jesuits also had one of their two residences at Hội An.[37] In 1640, Nguyễn lord Nguyễn Phúc Lan ordered to close all Dutch stores and factories in Hội An, ban the Dutch for trading in Cochinchina because he suspected the VOC allying with the Trịnh lord in the north.[38] In the 17th century, Polish Jesuit missionary Wojciech Męciński was believed to visited Hội An.[39]

In the 18th century, Hội An was considered by Chinese and Japanese merchants to be the best destination for trading in all of Southeast Asia, even Asia.

Trading activities and handicraft manufacturing had been shifted from Tonkin to Hội An.[27] The city also rose to prominence as a powerful and exclusive trade conduit between Europe, China, India, and Japan, especially for the ceramic industry. Shipwreck discoveries have shown that Vietnamese and Asian ceramics were transported from Hội An to as far as Sinai, Egypt.[40] Hội An's importance waned sharply at the end of the 18th century because of the collapse of Nguyễn rule (thanks to the Tây Sơn Rebellion – which was opposed to foreign trade).

Then, with the triumph of Emperor Gia Long, he repaid the French for their aid by giving them exclusive trade rights to the nearby port town of Đà Nẵng. Đà Nẵng became the new centre of trade (and later French influence) in central Vietnam while Hội An was a forgotten backwater. Local historians also say that Hội An lost its status as a desirable trade port due to silting up of the river mouth. The result was that Hội An remained almost untouched by the changes to Vietnam over the next 200 years. The efforts to revive the city were only done by a late Polish architect and influential cultural educator, Kazimierz Kwiatkowski, who finally brought back Hội An to the world. There is still a statue for the late Polish architect in the city, and remains a symbol of the relationship between Poland and Vietnam, which share many historical commons despite its distance.[41]

Beginning in the early 17th century, colonization of the area by Vietnamese settlers gradually isolated the Khmer of the Mekong Delta from their brethren in Cambodia proper and resulted in their becoming a minority in the delta.

In 1623, King Chey Chettha II of Cambodia (1618–28) allowed Vietnamese refugees fleeing the Trịnh–Nguyễn civil war in Vietnam to settle in the area of Prey Nokor and to set up a customs house there.[42] Increasing waves of Vietnamese settlers, which the Cambodian kingdom could not impede because it was weakened by war with Thailand, slowly Vietnamized the area. In time, Prey Nokor became known as Saigon. Prey Nokor was the most important commercial seaport to the Khmers.

The loss of the city and the rest of the Mekong Delta cut off Cambodia's access to the East Sea. Subsequently, the only remaining Khmers' sea access was south-westerly at the Gulf of Thailand e.g. at Kampong Saom and Kep. In 1698, Nguyễn Hữu Cảnh, a Vietnamese noble and explorer, was sent by the Nguyễn rulers of Huế by ship[43] to establish Vietnamese administrative structures in the area, thus detaching the area from Cambodia, which was not strong enough to intervene. He is often credited with the expansion of Saigon into a significant settlement of Kinh and Hoa people. A large Vauban citadel called Gia Định was built[44] by Victor Olivier de Puymanel, one of the Nguyễn Ánh's French mercenaries. The citadel was later destroyed by the French following the Battle of Kỳ Hòa (see Citadel of Saigon).

Initially called Gia Dinh, the Vietnamese city became Saigon in the 18th century. At the time, the population of Gia Định was around 200,000 people with 35,000 households.[45] Vietnamese people began settling in the Mekong Delta region, at least since 1623 when it was still uninhabited region of Cambodia. In 1707, Principality of Hà Tiên was set up by a Chinese refugee Mạc Cửu and his family, declared loyal to the Nguyen lord. Since that the Mekong Delta region now is belonged to Vietnam, but was treated as an autonomous principality.[46]

For centuries the Nguyễn's economy mostly depended on profitable semi-industrial and international trade, didn't pay attention for the large number of landless peasants.[47] Until later 18th century, due to deadly epidemic, severe flood in Red River Delta, the immense corruption of the government and the rise of Tây Sơn peasant rebellion in Southern Vietnam, that later spread entire country, devastated most of the economy and international trading, played a important role for the collapse of the dynasty.[a]

Notes[edit]

- ↑ Annam (Vietnam) had nominal tributary relations with dynasties in China. See #Foreign relations.

References[edit]

- ↑ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp 509

- ↑ Việt Nam sử lược, p. 96.

- ↑ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp 361.

- ↑ Mindy Chen-Wishart, Alexander Loke, Stefan Vogenauer, 2018, Formation and Third Party Beneficiaries, pp 450.

- ↑ Ben Kiernan (2017), Viet Nam: A History from Earliest Times to the Present, pp 205-208

- ↑ Ronald J. Cima (1989), Vietnam: a country study, trang 19.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư, Ngô Sĩ Liên, 1993, volume XI, 六月,定文武服色,自一品至三品著紅衣,四五品著綠衣,餘著青衣

- ↑ Ming Shilu - Yingzong era - vol 90, 7th year of Zhengtong. 《明史、安南國使臣黎昚陛辤,命賫敕并皮弁冠服、金織襲衣等物歸賜其安南國王黎麟》

- ↑ Trần, Quang Đức (2013) (in vietnamese) Ngàn năm áo mũ, Vietnam: Công Ty Văn Hóa và Truyền Thông Nhã Nam, pp. 156 ISBN: 978-1629883700.

- ↑ Đào, Phương Bình (1977) Thơ văn Lý Trần, 1, Hanoi: Nhà xuất bản Khoa học Xã hội, pp. 58

- ↑ George Dutton (2006) The Tay Son Uprising: Society and Rebellion in Eighteenth-Century Vietnam (Southeast Asia: Politics, Meaning, and Memory), Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press

- ↑ The Han Tu version of Hoàng Lê nhất thống chí

- ↑ Hội đồng Giám mục Việt Nam: Nhật ký Ad Limina 5.3.2018

- ↑ Franco-Vietnamese schools

- ↑ The history of gunpowder military using of Vietnam (in Vietnamese). Thanh Bình (10 March 2013).

- ↑ Military Technology Transfers from Ming China and the Emergence of Northern Mainland Southeast Asia (c. 1390-1527) Sun Laichen Journal of Southeast Asian Studies Vol. 34, No. 3 (Oct., 2003), pp. 495–517 Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of Department of History, National University of Singapore Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20072535 Page Count: 23

- ↑ Tran, 2006, p. 107

- ↑ Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư, vol 4

- ↑ Hoàng thành Thăng Long (8 August 2013). 10th-century Egyptian and Muslim ceramics found in Hanoi.

- ↑ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, vol 8-10

- ↑ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 364

- ↑ Brook 1998, p. 206

- ↑ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 369

- ↑ Ben Kiernan (2009) Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur, Yale University Press, p. 109 Retrieved on January 9, 2011. ISBN: 0-300-14425-3.

- ↑ Phạm Công Trứ, 1993, Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư, vol 15

- ↑ a b c d e Hoàng Anh Tuấn (2007) Silk for Silver: Dutch-Vietnamese Relations ; 1637 - 1700, Brill Co. ISBN: 978-9004156012.

- ↑ Tú Khôi, [ http://daibieunhandan.vn/default.aspx?tabid=77&NewsId=97265 Chuyện đi sứ của cha ông], Đại biểu nhân dân, truy cập ngày 26 tháng 6 năm 2015.

- ↑ Dupuy, p. 653.

- ↑ History of Vietnam, 2017, p. 240

- ↑ History of Vietnam, 2017, p. 262-264

- ↑ Bruce McFarland Lockhart, William J. Duiker, The A to Z of Viêt Nam, Scarecrow Press, 2010, pages 40, 365–366

- ↑ William Dampier, 1688, p. 70–88.

- ↑ 사헌부에서 전 제주 목사 이기빈과 전 판관 문희현의 치죄를 청하여 윤허하다「……그런데 이기빈과 문희현 등은 처음에는 예우하면서 여러 날 접대하다가 배에 가득 실은 보화를 보고는 도리어 재물에 욕심이 생겨 꾀어다가 모조리 죽이고는 그 물화를 몰수하였는데, 무고한 수백 명의 인명을 함께 죽이고서 자취를 없애려고 그 배까지 불태우고서는 끝내는 왜구를 잡았다고 말을 꾸며서 군공을 나열하여 거짓으로 조정에 보고했습니다.……」

- ↑ Spencer Tucker, "Vietnam", University Press of Kentucky, 1999, ISBN 0-8131-0966-3, p. 22

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ Roland Jacques Portuguese pioneers of Vietnamese linguistics prior to 1650 2002 Page 28 "At the time Pina wrote, early 1623, the Jesuits had two main residences, one in Hội An in Quàng Nam, the other at Quy Nhon."

- ↑ Đào Trinh Nhất 2015, p. 47.

- ↑ http://misjejezuici.blogspot.com/2012/07/wojciech-mecinski.html

- ↑ Li Tana (1998). Nguyen Cochinchina p. 69.

- ↑ https://culture.pl/en/artist/kazimierz-kwiatkowski

- ↑ Mai Thục, Vương miện lưu đày: truyện lịch sử, Nhà xuất bản Văn hóa – thông tin, 2004, p.580; Giáo sư Hoàng Xuân Việt, Nguyễn Minh Tiến hiệu đính,Tìm hiểu lịch sử chữ quốc ngữ, Ho Chi Minh City, Công ty Văn hóa Hương Trang, pp.31–33; Helen Jarvis, Cambodia, Clio Press, 1997, p.xxiii.

- ↑ The first settlers, Archived copy. Archived from the original on 29 September 2008. Retrieved on 2008-09-25.

- ↑ Ho Chi Minh City and around Guide – Vietnam Travel. Rough Guides. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved on 27 February 2016.

- ↑ Lịch sử hình thành đất Sài Gòn. Website Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh (22 May 2014). Archived from the original on 1 February 2010.

- ↑ Choi, p. 23-24

- ↑ HA. Tuấn 2007, p.26