User:Allixpeeke

Pages[edit]

Pages I have improved[edit]

Categories I have improved[edit]

Pages or categories that must be added[edit]

Music[edit]

The Year 1812 (1880)[edit]

The Year 1812 (festival overture in E♭ major, Op. 49 by Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky),[1] popularly known as the 1812 Overture or the Overture of 1812, is an overture written in 1880 to commemorate Russia's defense of its motherland against Napoleon's invading Grande Armée in 1812. It has also become a common accompaniment to fireworks displays, including those in the United States during Independence Day celebrations. The piece has no connection to the War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom.

The overture debuted in Moscow on 20 August 1882,[2] conducted by Ippolit Al'tani under a tent near the unfinished Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, which also memorialised the 1812 defense of Russia.[3] It was personally conducted by Tchaikovsky in 1891 at the opening of Carnegie Hall in New York City.[4] The overture is best known for its climactic volley of cannon fire, ringing chimes, and brass fanfare finale.

This performance from the Skidmore College Orchestra is far more recent. Both the original work and this performance are in the public domain.

Another rendition of the song appears in the film V for Vendetta.

See also[edit]

“Jim Calamaro”[edit]

Art[edit]

Prometheus bringt der Menschheit das Feuer (circa 1817)[edit]

See also[edit]

- Prometheus (mythology) on Wikicommons

- Prometheus on Wikipedia

The Storming of the Bastille (1789)[edit]

Stuff to add[edit]

- Search

- Category:Storming_of_the_Bastille,_14_July_1789

- Category:Paintings of the Storming of the Bastille

- w:Storming of the Bastille

- File:Canal Street New Orleans Bastille Day Centennial Triumphal Arch.jpg

- File:Bastille Tumble 2010 Vive la Liberte.JPG

- Category:Bastille Day, France

Fête de la Fédération[edit]

- File:Le serment de La Fayette a la fete de la Federation 14 July 1790 French School 18th century.jpg

La Vérité (1870)[edit]

The culmination of Jules Joseph Lefebvre's public acclaim occurred when Lefebvre painted La Vérité (Truth) in 1870.[5] The painting attracted rave reviews from both the critics and the public.[5] The model who posed for the painting, Sophie Croizette, was the well-known actress at the time.[5] The painting depicts Truth standing in the nude and holding the shining globe of above her head. Later that year, Lefebvre received the Legion of Honor award in recognition of his artistic contribution.[5]

See also[edit]

La Liberté éclairant le monde (1886)[edit]

La Liberté éclairant le monde (Liberty Enlightening the World, completed in 1886), designed by Frédéric Bartholdi, is a colossal neoclassical sculpture on Liberty Island in the middle of New York Harbor, in Manhattan, New York City. The statue, dedicated on 28 October 1886, was a gift to the United States from the people, not the government, of France. (Unfortunately, the base, which was constructed by Americans, did utilise tax dollars.)

The statue is of a robed female figure representing Libertas, the Roman goddess of freedom, who bears a torch and a tabula ansata (a tablet evoking the law) upon which is inscribed the date of the United States Declaration of Independence: July 4, 1776. A broken chain lies at her feet. The statue is an icon of freedom. It also served as a welcoming signal for immigrants to America arriving from abroad.

This statue is one inside of which people can go. While visitors are permitted to ascend to the crown, public access to the balcony surrounding the torch has been barred for safety reasons since 1916.

Since construction, the torch has been changed. The original torch is now located within the base of the monument.

Photographic images of the colossus[edit]

-

Majestic Liberty

-

The Statue of Liberty

-

Statue from below, front

-

Statue with Manhattan in the background

-

Statue in 2006

-

Statue from base, front

-

Profile Statue of Liberty in front of the sun

-

The Statue of Liberty from the east, embellished by golden sunset

-

Original torch, replaced in 1986

-

Bartholdi's statue, photograph by Robert N. Dennis (Robert N. Dennis collection of stereoscopic views)

-

Between 1876 and 1882, the Statue of Liberty arm was in Madison Square Park for fund-raising to complete the Statue; anyone could pay fifty cents to climb to the torch balcony

-

The Statue of Liberty's head, on exhibit at the Paris Exposition of 1878, photographed by Albert Fernique and published in 1883 in Frederic Bartholdi's Album des Travaux de Construction de la Statue Colossale de la Liberte destinee au Port de New-York (Paris)

Illustrations[edit]

-

1200 dpi black & white scan of David H. Montgomery’s The Beginner's American History (1904), page 43

-

The great Bartholdi statue, Liberty Enlightening the World. The gift of France to the American people. Copyright 1885 by Currier & Ives, N. Y.

1 print : chromolithograph. Speculative depiction published the year before the statue was erected. In this depiction the statue faces south; it actually faces east. -

A graffiti of the Statue of Liberty on the East Side Gallery of the Berlin Wall, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license by Gorgalore

-

A part of the Berlin Wall, Berlin, Germany, 1986. Photo by Nancy Wong.

-

Unveiling The Statue of Liberty (1886) by Edward Moran. Museum of the City of New York.

-

Lady Liberty Cracked (2001) by Julio Aguilera. Oil on canvas. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

-

Liberty Pointilist (1999) by Nevit Dilmen. Pointilist computer art. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

By Sem[?]

-

By William Armstrong for Studio 54

-

(21 May 2008) by Vis Unita Fortior, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license

Recreations[edit]

-

Created by (n)arcissus in 2010, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license

Note[edit]

There is also an image of Lady Liberty in shackles, denoting the rise of the police state in the United States; I aim to locate this image when time permits.

See also[edit]

- Liberty Enlightening the World on Wikipedia

- And Lady Liberty Wept, an album by Ken Foreman

- Weeping Statue of Liberty rubber stamp by Mary Vogel Lozinak

All is Vanity (1892)[edit]

From Wikipedia:

- In conventional parlance, vanity sometimes is used in a positive sense to refer to a rational concern for one's personal appearance, attractiveness and dress and is thus not the same as pride. However, it also refers to an excessive or irrational belief in one's own abilities or attractiveness in the eyes of others and may in so far be compared to pride. The term Vanity originates from the Latin word vanitas meaning emptiness, untruthfulness, futility, foolishness and empty pride.[6] Here empty pride means a fake pride, in the sense of vainglory, unjustified by one's own achievements and actions, but sought by pretense and appeals to superficial characteristics.

- In many religions, vanity is considered a form of self-idolatry, in which one rejects God for the sake of one's own image, and thereby becomes divorced from the graces of God. The stories of Lucifer and Narcissus (who gave us the term narcissism), and others, attend to a pernicious aspect of vanity. In Western art, vanity was often symbolized by a peacock, and in Biblical terms, by the Whore of Babylon. In secular allegory, vanity was considered one of the minor vices. During the Renaissance, vanity was invariably represented as a naked woman, sometimes seated or reclining on a couch. She attends to her hair with comb and mirror. The mirror is sometimes held by a demon or a putto. Other symbols of vanity include jewels, gold coins, a purse, and often by the figure of death himself.

- Often we find an inscription on a scroll that reads Omnia Vanitas ("All is Vanity"), a quote from the Latin translation of the Book of Ecclesiastes.[7] Although that phrase, itself depicted in a type of still life, vanitas, originally referred not to obsession with one's appearance, but to the ultimate fruitlessness of man's efforts in this world, the phrase summarizes the complete preoccupation of the subject of the picture.

- "The artist invites us to pay lip-service to condemning her," writes Edwin Mullins, "while offering us full permission to drool over her. She admires herself in the glass, while we treat the picture that purports to incriminate her as another kind of glass—a window—through which we peer and secretly desire her."[8] The theme of the recumbent woman often merged artistically with the non-allegorical one of a reclining Venus.

- In his table of the Seven Deadly Sins, Hieronymus Bosch depicts a bourgeois woman admiring herself in a mirror held up by a devil. Behind her is an open jewelry box. A painting attributed to Nicolas Tournier, which hangs in the Ashmolean Museum, is An Allegory of Justice and Vanity. A young woman holds a balance, symbolizing justice; she does not look at the mirror or the skull on the table before her. Vermeer's famous painting Girl with a Pearl Earring is sometimes believed to depict the sin of vanity, as the young girl has adorned herself before a glass without further positive allegorical attributes.[9] All is Vanity, by Charles Allan Gilbert (1873–1929), carries on this theme. An optical illusion, the painting depicts what appears to be a large grinning skull. Upon closer examination, it reveals itself to be a young woman gazing at her reflection in the mirror.

- Such artistic works served to warn viewers of the ephemeral nature of youthful beauty, as well as the brevity of human life and the inevitability of death.

Vanitas[edit]

Tank Man (1989)[edit]

The Tank Man, or the Unknown Protester, is the nickname of a heroic, anonymous man who stood on Chang'an Avenue in front of a column of tanks on 5 June 1989, the morning after the Chinese military had suppressed the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 by force. The man achieved widespread international recognition due to the videotape and photographs taken of the incident. Some have identified the man as Wang Weilin (王維林),[10] but the name has not been confirmed and little is known about him or of his fate after the confrontation that day. It is not even known whether this brave individual is alive. In April 1998, Time included the "Unknown Rebel" in a feature titled Time 100: The Most Important People of the Century.[11]

The man stood in the middle of the wide avenue, directly in the path of a column of approaching Type 59 tanks. He held two shopping bags, one in each hand.[12] As the tanks came to a stop, the man gestured towards the tanks with his bags. In response, the lead tank attempted to drive around the man, but the man repeatedly stepped into the path of the tank in a show of nonviolent action.[11] After repeatedly attempting to go around rather than crush the man, the lead tank stopped its engines, and the armored vehicles behind it seemed to follow suit. There was a short pause with the man and the tanks having reached a quiet, still impasse. Having successfully brought the column to a halt, the man climbed onto the hull of the buttoned-up lead tank and, after briefly stopping at the driver's hatch, appeared in video footage of the incident to call into various ports in the tank's turret. He then climbed atop the turret and seemed to have a short conversation with a crew member at the gunner's hatch. After ending the conversation, the man descended from the tank. The tank commander briefly emerged from his hatch, and the tanks restarted their engines, ready to continue on. At that point, the man, who was still standing within a meter or two from the side of the lead tank, leapt in front of the vehicle once again and quickly reestablished the man–tank standoff. Video footage shows that two figures in blue attire (identities also unknown) then pulled the man away and disappeared with him into a nearby crowd; the tanks continued on their way.[11] Whether the man ultimately escaped, was imprisoned, was tortured, or was executed remains unknown.

Internationally, the image of the lone man in front of the tank is widely considered one of the iconic images of the 20th century.[13][14][15] Five photographers managed to capture the event on film and get their pictures published in its aftermath, the first four capturing the event from relatively the same angle and released soon after the event,[13], and the fifth released on 4 June 2009 depicting the event from the ground level.[16]

The most used photograph of the event was taken by Jeff Widener of the Associated Press, from a sixth floor balcony of the Beijing Hotel, about half a mile (800 meters) away from the scene. Widener was injured and suffering from flu. The image was taken using a Nikon FE2 camera[17] through a Nikkor 400mm 5.6 ED IF lens and TC-301 teleconverter. Low on film, a friend hastily obtained a roll of Fuji 100 ASA color negative film, allowing him to make the shot.[13] Although he was concerned that his shots were not good, his image was syndicated to a large number of newspapers around the world, and was said to have appeared on the front page of all European papers.[13] Widener won the Pulitzer Prize.[18]

Another version was taken by Stuart Franklin of Magnum Photos from the fifth floor of the Beijing Hotel. His has a wider field of view than Widener's, showing that the man was blocking a long line of tanks, not merely a few. His roll of film was smuggled out of the country by a French student, concealed in a box of tea.[13]

Charlie Cole, who was on the same balcony as Stuart Franklin and working for Newsweek, hid his roll of film containing Tank Man in a Beijing Hotel toilet, sacrificing an unused roll of film and undeveloped images of wounded protesters when the PSB raided his room, destroyed the two rolls of film just mentioned, and forced him to sign a confession. Cole was able to retrieve the roll with Tank Man and have it sent to Newsweek.[19][13] He won a World Press Award for a similar photo.[20] It was featured in Life's "100 Photographs That Changed the World" in 2003.

Arthur Tsang Hin Wah of Reuters took several shots from room 1111[18] of the Beijing Hotel, but only the shot of Tank Man climbing the tank was chosen.[13] It was not until several hours later that the photo of the man standing in front of the tank was finally chosen. When the staff noticed Widener's work, they re-checked Wah's negative to see if it was of the same moment as Widener's. Recently (March 20, 2013), in an interview by the Hong Kong Press Photographers Association (HKPPA), Wah told the story and added further detail. He told HKPPA that on the night of June 3, 1989, he was beaten by students while taking photos and was bleeding. A "foreign" photographer accompanying him suddenly said "I am not gonna die for your country" and left. Wah returned to the hotel. When he decided to go out again, the public security stopped him, so he stayed in his room, stood next to the window, and eventually witnessed the Tank Man standoff, of which he took several shots on June 4, 1989.[18]

On June 4, 2009, in connection with the 20th anniversary of the protests, Associated Press reporter Terril Jones revealed a photo he took showing the Tank Man from ground level, a different angle than all of the other known photos of the Tank Man. Jones has written that he was not aware of what he had captured until a month later when printing his photos.[21]

Variations of the scene were also recorded by BBC film crews and transmitted across the world. One witness recounts seeing Chinese tanks early on June 4 crushing vehicles and people, just one day before this man stood in front of the tank column.[22]

Unfortunately, the memory of the event appears to have faded in China, especially among younger Chinese people, due to lack of public discussion.[23] Images of the protest on the Internet have been censored in China.[24] When undergraduate students at Beijing University, which was at the center of the incident, were shown copies of the iconic photograph some years afterwards, they "were genuinely mystified."[25] One of the students thought that the image was "artwork." It is noted in the documentary Frontline: The Tank Man, that he whispered to the student next to him "89"—which led the interviewer to surmise that the student may have concealed his knowledge of the event. One theory as to why the "Unknown Rebel" (if still alive) has never come forward is that he is unaware of his international recognition.[24]

Art based on Tank Man[edit]

A fictionalised version of the fate of both the Tank Man and a soldier in the tank is told in Lucy Kirkwood's 2013 play Chimerica.

See also[edit]

- Tiananmen Square on Wikicommons

- Tank Man on Wikipedia

- Tank Man (now with more raw footage) on YouTube

- More images of Castillo's statue on Google Images

- "Behind the Scenes: Tank Man of Tiananmen", contains the first four Tank Man photo released

- "Behind the Scenes: A New Angle on History", contains the fifth Tank Man photo by Terril Jones

- "Four Men With Cameras And An Elephant", contains a couple of Wah's photos depicting Tank Man climbing onto the tank

- Life magazine's "100 Photographs that Changed the World" on Wikipedia

- Lego

They’re Made Out of Meat (2009)[edit]

"They're Made Out of Meat" is a Nebula Award-nominated short story by Terry Bisson. It was originally published in OMNI.[26] It consists entirely of dialogue between two characters, sentient beings capable of travelling faster than light who are on a mission to "contact, welcome and log in any and all sentient races or multibeings in this quadrant of the Universe." They converse briefly on their bizarre discovery of carbon-based life, which they refer to incredulously as "thinking meat". They agree to "erase the records and forget the whole thing", marking the Solar System "unoccupied".[27]

They’re Made Out of Meat is a work of digital or computer art designed in 2009 by Alexander S. Peak. It was inspired by the Terry Bisson story of the same name, and depicts the two beings as orbs of energy, one fuchsia and the other teal. Peak, who described the short story as "brilliant", was inspired by the anti-collectivist themes of the story and how it "showcases the inherent irrationality of prejudice".[28]

See also[edit]

- "They're Made Out of Meat" on Wikipedia

- "They're Made Out of Meat" by Terry Bisson (full text)

Art by Francisco de Goya (1746–1828)[edit]

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes (/ˈɡɔɪə/; 30 March 1746–16 April 1828) was a Spanish romantic painter and printmaker. Often referred to as both the last of the Old Masters and the first of the moderns, Goya is considered the most important Spanish artist of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Los Caprichos (The Whims)[edit]

In 1799, Goya ran an announcement for his Caprichos in the Diario de Madrid in which he declared,

The author is convinced that it is as proper for painting to criticize human error and vice as for poetry and prose to do so, although criticism is usually taken to be exclusively the business of literature. He has selected from amongst the innumerable foibles and follies to be found in any civilized society, and from the common prejudices and deceitful practices which custom, ignorance, or self-interest have made usual, those subjects which he feels to be the most suitable material for satire, and which, at the same time, stimulate the artist's imagination.[3]

-

Capricho No. 3: Que viene el coco (Here comes the bogeyman, c. 1799) by Francisco de Goya. Etching and aquatint. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

-

Capricho No. 43: El sueño de la razón produce monstruos (The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, c. 1799) by Francisco de Goya. The full epigraph from the Prado etching version reads: "Fantasy abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters; united with her, she is the mother of the arts and the origin of their marvels."[1] Etching, aquatint, drypoint, and burin. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

-

Capricho No. 48: Soplones (Snitches, c. 1799) by Francisco de Goya. Etching and burnished aquatint. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

-

Capricho No. 49: Duendecitos (Hobgoblins, c. 1799) by Francisco de Goya. Etching and aquatint. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

-

Capricho No. 51: Se repulen (They spruce themselves up, c. 1799) by Francisco de Goya. Etching, burnished aquatint, and burin. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

-

Capricho No. 70: Devota profesión (Devout profession, c. 1799) by Francisco de Goya. Etching, aquatint, and drypoint. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

Los Desastres de la Guerra (The Disasters of War)[edit]

A series of 82 prints created between 1810 and 1820.

-

El Desastre de la Guerra No. 2: Con razon ó sin ella (With reason or without her, 1810, published 1863) by Francisco de Goya. Etching, lavis, drypoint, burin, and burnisher. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

-

El Desastre de la Guerra No. 9: No quieren (They do not want to, 1810, published 1863) by Francisco de Goya. Etching, burnished aquatint, drypoint, burin, and burnisher. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

-

El Desastre de la Guerra No. 12: Para eso habéis nacido (This is what you were born for, 1810, published 1863) by Francisco de Goya. Etching, drypoint, and burin. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

-

El Desastre de la Guerra No. 63: Muertos recogidos (The dead collected, 1811–12, published 1863) by Francisco de Goya. Etching and burnished aquatint. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

-

El Desastre de la Guerra No. 64: Carretadas al cementerio (Cartloads for the cemetery, 1811–12, published 1863) by Francisco de Goya. Etching, aquatint, drypoint, burin, and burnisher on a defective and pitted plate. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

-

El Desastre de la Guerra No. 71: Contra el bien general (Against the common good, after 1814–15, published 1863) by Francisco de Goya. Etching and burnisher. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

-

El Desastre de la Guerra No. 72: Las resultas (The consequences, after 1814–15, published 1863) by Francisco de Goya. Etching. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

-

El Desastre de la Guerra No. 79: Murió la Verdad (The truth has died, after 1814–15, published 1863) by Francisco de Goya. Etching and burnisher. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

-

El Desastre de la Guerra No. 80: ¿Si resucitará? ( Will she live again?, 1810–20, published 1863) by Francisco de Goya. Etching and burnisher. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Pinturas Negras (Black Paintings)[edit]

-

Aquelarre o El gran cabrón (Witches' Sabbath (literally Coven) or The Great He-Goat (literally The Great Bastard), 1821–1823) by Francisco de Goya. Oil on plaster wall, transferred to canvas. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

-

Untitled (called Saturn verschlingt eines seiner Kinder (Saturn Devouring His Son), 1819–1823) by Francisco de Goya. Oil mural transferred to canvas depicting the Titan Cronus. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

Other art[edit]

-

Cristo crucificado (Christ Crucified, 1780) by Francisco de Goya. Oil on canvas. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

-

Interior de cárcel (Prison Interior, 1793–1794) by Francisco de Goya. Oil on canvas. Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle.

-

Corral de locos (Yard with Lunatics, c. 1794) by Francisco de Goya. In one of his letters, Goya described the painting as "a yard with lunatics, in which two nude men fight with their warden beating them." Oil on tin-plated iron. Meadows Museum, Dallas, Texas.

-

El Aquelarre (Witches' Sabbath (literally The Coven), 1797–1798) by Francisco de Goya. Oil on canvas. Museo Lázaro Galdiano, Madrid.

-

La lámpara del Diablo (The Devil's Lamp, also known as The Bewitched Man, c. 1798 ) by Francisco de Goya. Oil on canvas depicting a scene from the play El hechizado por fuerza (The man bewitched by force) by Antonio de Zamora. National Gallery, London.

-

La Verdad, el Tiempo y la Historia (Truth, Time and History, 1812–1814) by Francisco de Goya. Oil on canvas. Nationalmuseum, Stockholm.

-

Auto de fe de la Inquisición (The Inquisition Tribunal, 1812–1819) by Francisco de Goya. Oil on panel. Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid.

-

Casa de locos (The Madhouse, 1812–1819) by Francisco de Goya. Oil on panel. Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid.

-

El tres de mayo de 1808 en Madrid (The Third of May 1808 in Madrid, 1814) by Francisco de Goya. Oil on canvas depicting the French Imperial reprisal against Spaniards in Madrid who'd dared to rise the day prior against the invasion of French troops. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

-

El Coloso (The Colossus, 1814–1818) by Francisco de Goya. Burnished aquatint etching.

Art by Jeroen van Valkenburg (1973–)[edit]

Jeroen van Valkenburg (Leiden, 1973) is a modern painter inspired by mythology and ancient sagas whose work has been exhibited in galleries in Holland and abroad.

-

The Astral Sleep (1998) by Jeroen van Valkenburg. Oil painting representing the cosmic spirit of a pantheist god. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic licence.

-

Icon (1999) by Jeroen van Valkenburg. Oil painting representing the cosmic spirit of a pantheist god. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic licence.

-

Lost (1999) by Jeroen van Valkenburg. Oil painting representing divine duality common in Wicca. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic licence.

-

Nightspawn (1999) by Jeroen van Valkenburg. Oil painting representing divine duality common in Wicca. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic licence.

-

The Realm of Rane (1999) by Jeroen van Valkenburg. Oil painting representing the Norse goddess Rán (and connecting her to the Wiccan goddess). Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic licence.

-

Divina (2000) by Jeroen van Valkenburg. Oil painting representing the multiple manifestations of the neopagan "mother goddess" (perhaps identifiable also with the "Triple Goddess"). Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic licence.

-

Icon II (2000) by Jeroen van Valkenburg. Oil painting representing the cosmic spirit of a pantheist god. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic licence.

-

Lifandi Lif Undir Hamri (Live Life Under the Hammer, 2000) by Jeroen van Valkenburg. Oil painting representing Mjölnir (Thor's hammer) from Norse mythology. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic licence.

-

The Realm of Rane II (2002) by Jeroen van Valkenburg. Oil painting representing the Norse goddess Rán (and connecting her to the Wiccan goddess). Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic licence.

-

The Golden Bough (2004) by Jeroen van Valkenburg. Oil painting representing the "triple aspects" of the Wiccan Goddess: the Maiden, the Mother, and the Crone. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic licence.

-

Yggdrasil (2005) by Jeroen van Valkenburg. Oil painting representing the Yggdrasil, a cosmic tree that connects the Níu Heimar (Nine Worlds) of Norse mythology. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic licence.

- External links

Art by Sascha Grosser (1973–)[edit]

Note: Titles presented of Grosser's works are assumed to be correct, but have not been verified. The year each work was produced is also uncertain.

-

Bluquader by Sascha Grosser. Licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License and the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license; one may select the license of her or his choice.

-

Mechanique-ateliereinraum by Sascha Grosser. Licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License and the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license; one may select the license of her or his choice.

-

listen to the sound of night by Sascha Grosser. Licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License and the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license; one may select the license of her or his choice.

-

red oszillox by Sascha Grosser. Licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License and the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license; one may select the license of her or his choice.

-

screwed blue by Sascha Grosser. Licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License and the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license; one may select the license of her or his choice.

-

By Sascha Grosser. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

By Sascha Grosser. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

By Sascha Grosser. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

By Sascha Grosser. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

By Sascha Grosser. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

By Sascha Grosser. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

By Sascha Grosser. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

By Sascha Grosser. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

By Sascha Grosser. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

By Sascha Grosser. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

By Sascha Grosser. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

Abstraktion4 by Sascha Grosser. Licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License and the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license; one may select the license of her or his choice.

-

By Sascha Grosser. Licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License and the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license; one may select the license of her or his choice.

-

Bahnelectra 1 by Sascha Grosser. Licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License and the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license; one may select the license of her or his choice.

-

Blick auf delfzjel 3 by Sascha Grosser. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

By Sascha Grosser. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

By Sascha Grosser. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

By Sascha Grosser. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

pewstone g2 (27 January 2014) by Sascha Grosser. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

Orchid tgt 1 (15 January 2014) by Sascha Grosser. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

(17 March 2014) by Sascha Grosser. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

a schnemu1 (2 March 2014) by Sascha Grosser. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Art by Romuald Bokėj[edit]

Note: Titles presented of Bokėj's works are assumed to be correct, but have not been verified. The year each work was produced is also uncertain.

-

Candle light (2005) by Romuald Bokėj. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic licence.

-

Burning candle (2005) by Romuald Bokėj. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic licence.

-

Flamenco dance (2006) by Romuald Bokėj. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic licence.

-

Flamenco passion (2006) by Romuald Bokėj. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic licence.

-

Seaweed (2006) by Romuald Bokėj. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic licence.

-

Ice in a barrel (2007) by Romuald Bokėj. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic licence.

-

Lake Gömmaren in Glömsta area, Huddinge, Sweden (2007) by Romuald Bokėj. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic licence.

-

Tree roots by the lake Gömmaren, Huddinge, Sweden (2007) by Romuald Bokėj. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic licence.

-

Equal rights for everybody! (2007) by Romuald Bokėj. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic licence. This artwork can be used to describe social movements (e.g., libertarianism, anarchism) for equal human rights, especially for black people, women and LGBT.

-

Peace art (collection of stones) in Näckrosen metro station, Stockholm, photographed April 2013 by Romuald Bokėj. Photograph licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic licence.

Art by Thomas Schultz[edit]

Note: Titles presented of Schultz's works are assumed to be correct, but have not been verified. The year each work was produced is also uncertain.

-

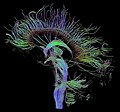

DTI-sagittal-xyzrgb (22 September 2006) by Thomas Schultz. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported licence.

-

DTI-sagittal-fibers (22 September 2006) by Thomas Schultz. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported licence.

-

DTI-axial-ellipsoids (22 September 2006) by Thomas Schultz. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported licence.

Other art[edit]

-

(Diagram of the Brain, circa 1300). Illumination on parchment, Cambridge University Library, England.

-

(Love Magic, first half of 15th century). Oil on panel.

-

(Kiss of Judas, first half of 15th century). Panel, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice, Italy.

-

(1490s). Illumination on parchment.

-

(Little girl with dead bird, between 1500 and 1525). Koninklijke Musea voor Schone Kunsten van België

-

Abraham Leading his Son Isaac to the Sacrifice (circa 1535). Musée du Louvre, Paris.

-

(Hairy Man from Munich, 1580s). Schloss Ambras, Innsbruck.

-

(Head of Medusa, 16th century). Oil on panel, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

-

Portrait of Mademoiselle de Mercœur (Françoise of Lorraine) future Duchess of Vendôme as an enfant (circa 1600).

-

(circa 1600).

-

(Portrait of the dead Caspar of Uchtenhagen in a coffin, 1603). Oil on canvas, Bad Freienwalde, Germany.

-

The Cholmondeley Ladies (circa 1600–1610). Oil on panel, Tate Britain, London.

-

Portret królowej Konstancji Austriaczki z papugą (circa 1615). Oil on canvas, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, Bavaria, Germany.

-

Sophie von Sachsen (1587-1635), Herzogin von Pommern-Stettin (circa 1615). Oil.

-

Portret królewicza Jana Kazimierza Wazy (circa 1619). Oil on canvas, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, Bavaria, Germany.

-

(1628). Oil on panel, Alte Pinakothek, Munich.

-

(Allegory of the Vanity of Earthly Things, circa1630). Oil on canvas, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Rome.

-

(The future Louis XIV of France as Dauphin, 1639). Oil.

-

The Meeting of Jacob and Rachel at the Well (1640s). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

-

(circa 1650).

-

(circa 1650).

-

(Between 1626 and 1656). Oil on canvas, Musée du Louvre, Paris.

-

(The Last Judgment, circa 1660). Egg tempera on wood, Ikonen-Museum Recklinghausen, Recklinghausen.

-

Kinderporträt Barbara von Orelli (1682). Schweizerisches Nationalmuseum, Zürich.

-

(Mocking of Christ, 17th century). Oil on canvas.

-

Affengesellschaft beim Spiel (Backgammon-playing Baboons, 17th century). Oil on panel.

-

(17th century). Oil.

-

(17th century). Oil on canvas.

-

(Charles II de Cossé, maréchal de France, 17th century). Oil.

-

(17th century).

-

(The Holy Trinity, circa 1700). Egg tempera on wood, Ikonen-Museum Recklinghausen, Recklinghausen.

-

Adlige Frau mit Schweinskopf, Bericht über vergebliche Heiratsversuche (1717). Engraving.

-

(1780). Engraving.

-

(Miniature of Benjamin Franklin, second half of 18th century). Watercolor on ivory, Muzeum Czartoryskich w Krakowie, Kraków.

-

The Muir portrait of Adam Smith (circa 1800). Oil on canvas, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh. The Muir portrait of Adam Smith is “so called after those who are known to have owned it. … We have no absolute confirmation, no positive actual proof, that the picture is of Adam Smith. We have definitive evidence that one such portrait of him existed. Beyond this, the most we should say is that the Muir portrait makes out quite the best claim to being an authentic portrait of Adam Smith [as] no other claimant has appeared with a comparable case” (A. L. Macfie, 1952).

-

El Aquelarre (The Coven, circa 1830–1845) attributed to Leonardo Alenza y Nieto. Oil on canvas.

-

The Field of Terror (1823), drawing by George Cattermole for Popular Tales and Romances of the Northern Nations, in Three Volumes (Vol. III, 1823).

-

(Gustave de Molinari, 19th century). Drawing.

-

(Gustave de Molinari, 19th century). Drawing.

-

Pandora (1872) by Jules Joseph Lefebvre. Oil on canvas, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires, Argentina. (Brighter version here.)

-

(Reclining Nude With Skull, circa 1890). Photo. Reproduced in Erotique: Masterpieces of Erotic Photography by Rod Ashford (ISBN 1-85868-577-X).

-

(Reclining Nude With Skull, circa 1890). Photo. Reproduced in Erotique: Masterpieces of Erotic Photography by Rod Ashford (ISBN 1-85868-577-X).

-

Pandora (1896) by John William Waterhouse. Oil on canvas.

-

This is a nineteenth century engraving of Pandora trying to close the box that she had opened out of curiosity. At left, the evils of the world taunt her as they escape. The engraving is based on a painting by F. S. Church.

-

Der Traum (8 October 2004) by Geo Goidaci. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Germany license.

-

El Libro Rosa (26 April 2013) by Charolet. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

Benjamin Franklin at the Court of France

-

(Adam Smith). Engraving. See also Profile of Adam Smith.

-

The dead life by Lemmens Martyn. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

By Spaceape.

-

Auditori municipal, Lleida. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported licence.

Other digital and computer art[edit]

-

(2001) by Nevit Dilmen. Pointilist computer art. Licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License and the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

The Canyon 02 (2006) by Nevit Dilmen. Pointilist computer art. Licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License and the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

Quantaseeding (14 July 2007) by Promytius. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

Variances 12 (29 December 2008) by Jgad. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

La siréne 1 (12 March 2009) by Jgad. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

First Daughter Inhales the Breath of the Citadel (2 June 2010) by ArtistEye. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

First Daughter Warns Juan in Orbit (7 June 2010) by ArtistEye. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

Danza de Salome (10 October 2010) by Quim Abella. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, 2.5 Generic, 2.0 Generic and 1.0 Generic licenses; one may select the license of her or his choice.

-

Green Spiky Explosion (23 October 2010) by Joseph El-Khouri. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 United States license.

-

Puissances mystérieuses (25 May 2011) by Jgad. Licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License and the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license; one may select the license of her or his choice.

-

(29 April 2012) by Jhona Lemole. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

el interior es lo que cuenta (12 June 2013) by Oscarredbaron. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

Dripping Paint (22 May 2012) by Mattes. Licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License.

-

Iridescence Fantasy (22 May 2012) by Mattes. Licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License and the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 license.

-

Der Stuhl (7 December 2013) by Geo Goidaci. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Germany license.

-

Alias la Patata by PierPaolo Voci. Licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License and the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license; one may select the license of her or his choice.

-

Io può, tu mi sa di no! by PierPaolo Voci. Licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License and the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license; one may select the license of her or his choice.

-

Alibaas by L'Avocat. Licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License and the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

-

BlueShift.png by James1011R. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

-

Starattack by Ubuntuist. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic license.

-

By IAmSoftChild. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Other photographs[edit]

Anarchist cheerleaders[edit]

Smells Like Teen Spirit[edit]

Other[edit]

Mugshots[edit]

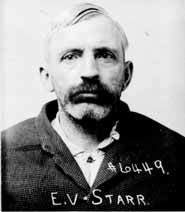

Mugshot of E. V. Starr (1918)[edit]

Earnest V. Starr (28 May 1870 – unknown) was a farmer and homesteader notable for being tried, convicted, and sentenced on 27 September 1918 to 10–20 years of hard labor in a state penitentiary as well as fined $500 plus court costs for the so-called crime of sedition by "utter[ing] contemptuous and slurring language about the flag [of the United States] and language calculated to bring the flag into contempt and disrepute." And what exactly, pray tell, was it that Starr said? Only this:

- What is this thing anyway? Nothing but a piece of cotton with a little paint on it, and some other marks in the corner there. I will not kiss that thing. It might be covered with microbes.

On 24 March 1918, Starr was confronted by approximately fifteen men in a local committee and questioned about his failure to make Liberty Bond contributions. Said mob demanded that Starr kiss a flag of the United States in order to demonstrate his loyalty to the U. S. government. Starr refused, uttering the quote above; six months later, he was tried for sedition, convicted in a jury trial. His habeas corpus petitions were denied by both the Montana Supreme Court and a U. S. District Court. His sentence was commuted by Governor Joseph M. Dixon on 4 June 1921 to 5–20 years making him immediately eligible for parole. He served thirty-five months of his sentence and was released 18 September 1921. No member of the mob that harassed him were ever punished for their unlawful or disorderly conduct.

Flags[edit]

-

Chesapeake Bay -

Chesapeake Bay -

Luna -

Luna -

Sol -

Sol

Maps[edit]

Ballot Access[edit]

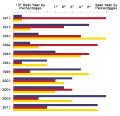

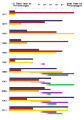

Libertarian Party[edit]

-

1972 -

1976 -

1980 -

1984 -

1988 -

1992 -

1996 -

2000 -

2004 -

2008 -

2012

Ron Paul[edit]

-

1988 -

2008 -

2012

Other[edit]

-

Personal Choice Party, 2004 -

Boston Tea Party, 2008 -

Objectivist Party, 2008 -

Objectivist Party, 2012

Election Results[edit]

Libertarian Party[edit]

Percentage of popular vote[edit]

▇ 0%

▇ 0.25%

▇ 0.5%

▇ 0.75%

▇ 1%

▇ 1.5%

▇ 2%

▇ 3%

▇ 4%

▇ 5%

▇ 6%

▇ 7%

▇ 8%

▇ 9%

▇ 10%

▇ 11%

▇ 12%

▇ 13%

▇ 14%

▇ 15%+

More available upon request.

-

1972

.0047% -

1976

.2116% -

1980

1.0648% -

1984

.2462% -

1988

.4714% -

1992

.2778% -

1996

.5045% -

2000

.3647% -

2004

.3248% -

2008

.3988% -

2012

.9885% -

1972–2012

.4571%

Raw vote count[edit]

▇ 0 votes

▇ 1,000 votes

▇ 2,000 votes

▇ 3,000 votes

▇ 4,000 votes

▇ 5,000 votes

▇ 6,000 votes

▇ 7,000 votes

▇ 8,000 votes

▇ 9,000 votes

▇ 10,000 votes

▇ 12,500 votes

▇ 15,000 votes

▇ 17,500 votes

▇ 20,000 votes

▇ 25,000 votes

▇ 30,000 votes

▇ 40,000 votes

▇ 50,000 votes

▇ 75,000 votes

▇ 100,000+ votes

More available upon request.

-

1972

3,674 votes -

1976

172,553 votes -

1980

921,128 votes -

1984

228,111 votes -

1988

431,750 votes -

1992

290,087 votes -

1996

485,759 votes -

2000

384,431 votes -

2004

397,265 votes -

2008

523,715 votes -

2012

1,275,971 votes

Ordinal ranking[edit]

▇ 8th place ▇ 7th place ▇ 6th place ▇ 5th place ▇ 4th place ▇ 3rd place

-

1972

10th place -

1976

4th place -

1980

4th place -

1984

3rd place -

1988

3rd place -

1992

4th place -

1996

5th place -

2000

5th place -

2004

4th place -

2008

4th place -

2012

3rd place

Ron Paul[edit]

Percentage of popular vote[edit]

▇ 0.00%

▇ 0.50%

▇ 1.00%

▇ 1.50%

▇ 2.00%

▇ 2.50%

▇ 3.00%

More available upon request.

-

1988

.4714% -

2008

.0323% -

2012

.0203% -

1988, 2008–2012

.1422%

Ordinal ranking[edit]

▇ 11th place ▇ 10th place ▇ 9th place ▇ 8th place ▇ 7th place ▇ 6th place ▇ 5th place ▇ 4th place ▇ 3rd place

-

1988

3rd place -

1988

8th place -

1988

9th place

Objectivist Party[edit]

Percentage of popular vote[edit]

▇ 0.00%

▇ 0.01%

▇ 0.02%

▇ 0.03%

▇ 0.04%

▇ 0.05%

More available upon request.

-

2008

.0006% -

2012

.0032% -

2008–2012

.0019%

Boston Tea Party[edit]

Percentage of popular vote[edit]

▇ 0.00%

▇ 0.01%

▇ 0.02%

▇ 0.03%

▇ 0.04%

More available upon request.

-

2008

.0018%

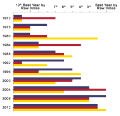

Home States[edit]

By Year[edit]

(United States of America)

▇ Gary Johnson, Libertarian

▇ Barack Obama, Democratic

▇ Mitt Romney, Republican

▇ Jill Stein, Green

▇ Virgil Goode, Constitution

▇ Rocky Anderson, Justice

- 2012 (expanded)

- 2008 (expanded)

- 2004 (expanded)

- 2000 (expanded)

- 1996 (expanded)

- 1992 (expanded)

- 1988 (expanded)

- 1984 (expanded)

- 1980 (expanded)

- 1976 (expanded)

- 1972 (expanded)

- 1968 (expanded)

- 1964 (expanded)

- 1960 (expanded)

- 1956 (expanded)

By Party[edit]

Combinations[edit]

▇ Libertarian

▇ Democratic

▇ Republican

|

| BTP | LP | |||||||||

|

| BTP | LP | OP | PCP | |||||||

|

| CP | DP | LP | RP | |||||||

|

| CP | DP | G/GPUSA | GPUS | LP | RP | |||||

|

| CP | LP | |||||||||

|

| DP | G/GPUSA | GPUS | LP | RP | ||||||

|

| DP | LP | |||||||||

|

| DP | LP | RP | ||||||||

|

| DP | RP | |||||||||

|

| G/GPUSA | GPUS | LP | ||||||||

|

| JP | LP | |||||||||

|

| LP | OP | |||||||||

|

| LP | PCP | |||||||||

|

| LP | RPUSA | |||||||||

|

| LP | RP |

Graphs and charts[edit]

Graphs and charts in physics[edit]

Pitch drop experiment[edit]

University of Queensland[edit]

-

With demarcation of years

-

With demarcation of years and months

-

With notation of major events

-

With demarcation of years and major events

-

With demarcation of years, months, and major events

Graphs and charts in politics[edit]

United States presidential election results (1972–2012)[edit]

United States presidential election popular vote counts (1972–2012)[edit]

Ordinal United States presidential election results (1972–2012)[edit]

Ordinal, interyear, intraparty comparisons of United States presidential election results[edit]

Comparing percentages of the popular vote[edit] |

Comparing raw popular vote counts[edit] |

Comparing ordinal rankings[edit] |

Images I may wish to alter and incorporate into my coat of arms, should I ever bother to create one[edit]

Note: Files below not showing up are on Wikipedia.

-

The coat of arms of the Cossé-Brissac family. I appreciate the yellow and black, colours symbolic of anarchist libertarianism. But, obviously, I would have to change the coat’s design significantly enough so as to eliminate reference to the Cossé-Brissac family.

-

The coat of arms of Vendeville, a commune in the Nord department in northern France. (Also other communes.)

-

The coat of arms of Limont-Fontaine, a commune in the Nord department in northern France. (Also other communes.)

-

The coat of arms of Lompret, a commune in the Nord department in northern France. (Also other communes.)

-

The coat of arms of Masny, a commune in the Nord department in northern France. (Also other communes.)

-

The coat of arms of Neuville-en-Avesnois, a commune in the Nord department in northern France. (Also other communes.)

-

The coat of arms of Marchiennes, a commune in the Nord department in northern France. (Also other communes.)

-

The coat of arms of Marly, a commune in the Nord department in northern France. (Also other communes.)

-

The coat of arms of Mons-en-Barœul and of Viesly, a pair of communes in the Nord department in northern France. (Also other communes.)

-

The coat of arms of Oisy, a commune in the Nord department in northern France. (Also other communes.) The counterchanging thing might be useful.

-

This might be helpful.

-

Looks cool.

-

Would, of course, require yellow.

Notes[edit]

- No crests, because crests are stupid and lame. That said, if I were to have a crest, it would totally be a bat.

- It would make sense to create a banner of arms to accompany my coat of arms. (See also heraldic flag.)

- Motto in English: Peace, Love, Anarchy, Natural Law, Free Markets

- Motto in Latin: Pax, Amor, Anarchia, Ius Naturale, Liberi Mercatus

See also[edit]

Category:Coats of arms Category:Heraldic shields w:Tincture (heraldry) w:Rule of tincture w:Escutcheon (heraldry) w:Banner of arms w:Heraldic flag w:Heraldic badge Category:Coats of arms of departments of France Category:Special or fictional coats of arms Category:Historical coats of arms Mises Category:Disputed coats of arms Category:Coats of arms by topic Category:SVG coat of arms elements and Category:Coat of arms elements to be classified stuff Category:Symbols

Stuff to be possibly added[edit]

- File:Mentag rubrum violaceum.jpg

- File:(1)Crow-1a.jpg

- File:Van Gogh - Starry Night - Google Art Project.jpg

- The Persistence of Memory

- File:Locatelli, Andrea - Magic Scene - c. 1741.jpg

- File:Frans II Francken – A Witches' Kitchen.jpg

- File:GLEYRE Charles Gabriel The Queen Of Sheba.jpg

- File:Waterhouse Hylas and the Nymphs Manchester Art Gallery 1896.15.jpg

- File:Gerome venus.jpg

- File:No43big-1d-B3-flat.jpg

- File:Le Voyage dans la lune.jpg

- File:Buddhabrot-W1000000-B100000-L20000-2000.jpg

- File:Apophysis 3D fractal ball.jpg

- File:Da Vinci Vitruve Luc Viatour.jpg

- File:Currier and Ives Liberty2.jpg (Statue of Liberty illustration)

- File:Adi Holzer Werksverzeichnis 835 Abrahams Opfer.jpg

- File:Adi Holzer Werksverzeichnis 849 Die Taufe.jpg

- File:Sandro Botticelli - La nascita di Venere - Google Art Project - edited.jpg

- File:Eugène Delacroix - La liberté guidant le peuple.jpg

- File:Édouard Manet - Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe.jpg

- File:Dame (Alice) Ellen Terry ('Choosing') by George Frederic Watts.jpg

- File:John-bell-II-B-6.jpg

- File:Chloé.jpg

- File:Lilith (John Collier painting).jpg

- File:Makart Fuenf Sinne.jpg

- File:William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905) - Dawn (1881).jpg

- File:William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905) - The Birth of Venus (1879).jpg

- File:Caspar David Friedrich 012.jpg

- Peace (various)

- Category:Peace (various)

- Love (various)

- Category:Love (various)

- Category:Surrealism

- Category:Political symbols

- Symbols

- Commons:Featured pictures/Natural phenomena

- Commons:Featured pictures/Historical

- Category:Art by Wikipedians

- File:London MMB 75 Granby Terrace.jpg

- Category:Moiré

- Category:Iridescence

- Art by User:Mojonavigator

- Category:Digital painting

- Category:Gimpressionist

- User:Nevit/Gimpressionist

- w:Liberty Statue (Budapest)

- w:Statue of Liberty (Mytilene)

- w:Beacon of Hope (sculpture)

- w:Vision of Peace (Indian God of Peace)

- w:Statue of Freedom

- Category:Liberty

- Category:Statues of Freedom

- Category:Allegories of liberty

- w:100 Photographs that Changed the World

- File:Calburn Lake PS.JPG

- File:Anoniem102.jpg (Woman with dogface)

- File:Radiometer 9965 Nevit.gif

- File:Neuron-SEM-2.png

- File:SurfaceTension.jpg

- File:Herz aus Feuer.jpg

- File:Soap bubble sky.jpg

- File:Taijitu polarity.PNG

- File:Natural yin and yang formation.PNG

- File:Neon Yin Yang.jpg

- File:Birth of Laozi.PNG

- File:Dschuang-Dsi-Schmetterlingstraum-Zhuangzi-Butterfly-Dream.jpg

- File:1921 photo of a fairy.jpg

- File:Cernunnos - by Jeroen van Valkenburg.PNG

- File:Red-blue sunset.jpg

- File:Dore enigma.jpg

- File:Heart Flow.jpg

- File:The Golden Bough - by Jeroen van Valkenburg.PNG

- Category:Kazimir Malevich

Statues[edit]

- File:Bad Woerishofen - Bronzestatue vor dem Kurhaus.jpg

- File:Rosenfelder Ring Berlin-Frf 096-147.JPG

- File:Jupp Zimmer Kaiserstrasse Trier.JPG

- File:Merrion Square maid.jpg

- File:Warofindep.jpg

- File:Mourning angel.jpg

- File:Hakone open air museum (16).jpg

- File:Hakone Unknown 02.jpg

- File:Hakone1.jpg

- File:Hakone2.jpg

- File:Hakone4.jpg

- File:FotoCH 17.JPG

- File:Dame op een brugje in Valkenburg.jpg

- File:Middelburg Lutherse kerklaan Skulptur.jpg

- File:Rotterdam kunstwerk vrouwentorso.jpg

- File:Haag - turtle garden.jpg

- File:Denhaag kunstwerk onbekend Guntersteinweg.jpg

- File:Object Röntgenstraat.jpg

- File:Denhaag kunstwerk onbekend binckhorstlaan.jpg

- File:Aalsmeer kunstwerk onbekend Jp Thijsselaan.jpg

- File:Alblasserdam kunstwerk onbekend sportlaan.jpg

- File:Barendrecht kunstwerk onbekend 2ebarendechtseweg 1e.jpg

- File:Barendrecht kunstwerk onbekend 2ebarendechtseweg 2e.jpg

- File:Barendrecht kunstwerk onbekend Harmonielaan.jpg

- File:Barendrecht kunstwerk onbekend Reling.jpg

- File:Bayreuth - Kunstwerk mit Uhr am Busbahnhof.jpg

- File:Denhaag kunstwerk onbekend gedempte gracht.jpg

- File:Dordrecht kunstwerk onbekend Heemskerckstraat .jpg

- File:Dordrecht kunstwerk onbekend maasstraat.jpg

- File:Dordrecht kunstwerk onbekend papeterspad5.jpg

- File:Dordrecht kunstwerk onbekend vogelplein.jpg

- File:Gorinchem kunstwerk onbekend2.jpg

- File:Hardinxveld kunstwerk groep personen.jpg

- File:Hardinxveld kunstwerk onbekend bij bibliotheek.jpg

- File:Hardinxveld kunstwerk pedaja.jpg

- File:Hillegom kunstwerk meer en dorp.jpg

- File:Hillegom kunstwerk witte engel.jpg

- File:Krimpen kunstwerk beeld ter ontmoeting.jpg

- File:Krimpen kunstwerk carese.jpg

- File:Krimpen kunstwerk huismussen.jpg

- File:Krimpen kunstwerk klokkestoel.jpg

- File:Krimpen kunstwerk plastiek.jpg

- File:Krimpen kunstwerk plastiek2.jpg

- File:Krimpen kunstwerk samenspel.jpg

- File:Krimpen kunstwerk sneeuwwitje en rozerood.jpg

- File:Krimpen kunstwerk speelplastiek gedeeld.jpg

- File:Lansingerland kunstwerk onbekend dorpsstraat.jpg

- File:Leiderdorp kunstwerk vier kinderen.jpg

- File:Längenfeldgasse 02.JPG

- File:Oegstgeest kunstwerk onbekend bij endegeest.jpg

- File:Oegstgeest kunstwerk onbekend endegeest.jpg

- File:Papendrecht kunstwerk onbekend Merwehoofd.jpg

- File:Ridderkerk kunstwerk onbekend kpn willemstraat.jpg

- File:Rijswijk kunstwerk onbekend1.jpg

- File:Rijswijk kunstwerk onbekend2.jpg

- File:Rotterdam kunstwerk christiaanstraat onbekend.jpg

- File:Sculpture au Jardin d'Agronomie Tropicale - L'Afrique.JPG

- File:Sculpture au Jardin d'Agronomie Tropicale - Persée 2.JPG

- File:Sliedrecht kunstwerk twee figuren.jpg

- File:Spijkenisse kunstwerk onbekend hoeklaan.jpg

- File:Spijkenisse kunstwerk onbekend schepenpad.jpg

- File:Spijkenisse kunstwerk spelende kinderen.jpg

- File:Statue St-Michel (Picpus).jpg

- File:Voorburg kunstwerk onbekend1 fonteynenburghlaan.jpg

- File:Wassenaar kunstwerk onbekend5 american-school.jpg

- File:Zwijndrecht kunstwerk nijverheid.jpg

- File:Zwijndrecht kunstwerk onbekend5.jpg

- File:Zwijndrecht kunstwerk schoolkinderen.jpg

Photos[edit]

- File:Victoria gaston and ferdinand 1852.jpg

- File:Duquesa de Nemours em seu leito de morte.JPG

- File:19th century Photograph - man.jpg

- File:19th century Photograph - woman.jpg

- File:Joseph Merrick carte de visite photo, c. 1889.jpg

- File:Lenin family.jpg

Maps[edit]

Music[edit]

Religious[edit]

- File:Zenphiloshophycircle.png

- File:TurtlesAllTheWayDown2.png

- File:Martin, John - Satan presiding at the Infernal Council - 1824.JPG

- Hell

- Category:Hell

- Category:Lucifer

- Category:The Devil

- w:Christ the Redeemer (statue)

- File:Mary Magdalene In The Cave.jpg

- File:Gerdt Hardorff Kreuzigung St Jacobi.jpg

- File:15th-century unknown painters - Crucifixion - WGA23758.jpg

- File:15th-century painters - Vir Dolorum (Man of Sorrows) - WGA15882.jpg

- File:15th-century painters - The Ascension of Christ - WGA15801.jpg

- File:15th-century unknown painters - Trinity Pietà (reverse) - WGA23728.jpg

- File:15th-century unknown painters - Trinity Pietà - WGA23727.jpg

- File:Unknown painter - Holy Trinity - WGA23839.jpg

- File:Venasque église Notre-Dame Crucifixion 1498.jpg

- File:12th century unknown painters - The Christ from the Vision of Ezekiel - WGA19728.jpg

- File:12th-century unknown painters - Angels - WGA19718.jpg

- File:Unknown painter - The Madonna della Salute - WGA23479.jpg

- File:Unknown painter - Ascension of Christ (detail) - WGA24082.jpg

- File:11th century unknown painters - Last Judgment (detail) - WGA19745.jpg

- File:11th century unknown painters - Last Supper - WGA19748.jpg

- File:11th century unknown painters - The Building of the Tower of Babel - WGA19706.jpg

- File:11th century unknown painters - The Creation of Adam and Eve - WGA19705.jpg

- File:EVE AND THE SERPENT 2013 REVISED.jpg

- File:William Blake Eve Tempted by the Serpent.jpg

- File:William Blake - The Temptation and Fall of Eve (Illustration to Milton's "Paradise Lost") - Google Art Project.jpg

- File:Albert von Keller Eva.jpg

- File:Keller-Maertyrerin.jpg

Documents[edit]

- Magna Carta (various)

- File:Declaration of Independence.jpg

- Category:United States Declaration of Independence (various)

- File:Articles of Confederation 1-5.jpg

- File:Articles of Confederation 5-6.jpg

- File:Articles of Confederation 7-9.jpg

- File:Articles of Confederation 9-9.jpg

- File:Articles of Confederation 9-13.jpg

- File:Articles of Confederation 13.jpg

Libertarian[edit]

- File:Broken-chains.gif (Note: Make yellow version)

- File:Libertarian Party Porcupine (USA).svg

- File:Libertarian Porupine Gadsden Flag 800.png

- File:En-Libertarian National Committee in a deadlock over how to address growing Bob Barr controversies.ogg

- File:En-Plans set in motion for the removal of Bob Barr as the Libertarian Partys U.S. presidential nominee.ogg

- File:Nolan chart-quiz.jpg

- Category:Libertarianism in the United States

- Category:Left-libertarianism

- File:Logo of alliance of the libertarian left.svg

- Category:Libertarians

- Category:Libertarianism by country

- Category:Books by Murray Rothbard

- Category:Murray Rothbard

- File:1983 libertarian presidential convention in NYC.jpg

- Category:Anarcho-capitalists

- Category:Anarcho-capitalism

- Category:Agorism

- Category:Libertarianism

- Category:Libertarian Party (United States)

- Category:Libertarians by country

- Category:Politicians of the Libertarian Party (United States)

- Category:Libertarians from the United States

- More libertarianism

- Category:Anarchist flags

V for Vendetta[edit]

- File:An0nyMouS.jpg

- File:The Gunpowder Plot Conspirators, 1605 from NPG.jpg

- File:The Gunpowder Plot Conspirators, 1605 from NPG (2).jpg

Science[edit]

Space[edit]

- Commons:Featured pictures/Astronomy

- Commons:Featured pictures/Space exploration

- Category:Cosmic microwave background

- Category:Hubble Deep Fields

- Category:Voyager Golden Record

- Category:Pioneer plaque (That drawing of human beings that got sent off into space)

- Category:Arecibo message (binary message sent into space)

- File:Eagle nebula pillars complete.jpg and File:Eagle nebula pillars.jpg

- File:VY Canis Majoris.jpg

- File:Earth's Location in the Universe VERTICAL (JPEG).jpg

Sol[edit]

- File:FraunhoferLinesDiagram.jpg

- File:William_Turner-_The_Angel,_Standing_in_the_Sun.JPG

- File:Paul_Klee_Der_Hof_(Sonne_im_Hof)_1913.jpg

- File:Leo_Gestel_Namiddagzon_1908.jpg

- File:JUL_Soul_Iris.png

- File:Soleil_levant_Claude_Monet.jpg

- File:Claude_Monet,_Impression,_soleil_levant,_1872.jpg

- File:Sunrise_(big).jpg

- File:Joseph_Mallord_William_Turner_-_Norham_Castle,_Sunrise_-_WGA23182.jpg

- File:Beacon,_off_Mount_Desert_Island_Frederic_Edwin_Church.jpg

- File:Autumn_Landscape-William_Louis_Sonntag.jpg

People[edit]

Lady Godiva[edit]

Prometheus[edit]

Montesquieu[edit]

Voltaire[edit]

- File:D'après Maurice Quentin de La Tour, Portrait de Voltaire (château de Ferney) -001.jpg

- File:D'après Maurice Quentin de La Tour, Portrait de Voltaire, détail du visage (château de Ferney).jpg

- File:D'après Maurice Quentin de La Tour, Portrait de Voltaire (c. 1737, musée Antoine Lécuyer).jpg

- File:D'après Nicolas de Largillière, portrait de Voltaire (Institut et Musée Voltaire) -001.jpg

- File:D'après Nicolas de Largillière, portrait de Voltaire (Institut et Musée Voltaire) -002.jpg

Garrison[edit]

Presidents[edit]

Scientists, mathematicians, and inventors[edit]

Krampus[edit]

- File:Svaty Mikulas 1885 Ales.png

- File:Mikuláš a Krampus 1900s.jpg

- File:Nikolaus krampus.jpg

- File:Krampus 1900s 2.jpg

- File:Mikuláš a Krampus 1901.jpg

- File:Krampus 1900s.jpg

- File:Nikolaus und Krampus.jpg

- File:Krampus 1900s 3.jpg

- File:Krampus 1900s 4.jpg

- File:Krampus-Postkarte um 1900.jpg

- File:Gruss vom Krampus.jpg

- File:Masopust držíme 31.jpg

- File:Jurij Šubic - Nikolo.jpg

- File:Poertschach Krampuslauf Perchten Mephisto 29112013 693.jpg

- File:Krampus Morzger Pass Salzburg 2008 09.jpg

- File:Krampus at Perchtenlauf Klagenfurt.jpg

- File:Sfilata Krampus a Dobbiaco 5.JPG

Love[edit]

- File:Love... for Valentines (4333751789).jpg

- File:Love-lust.jpg

- File:BuscemiHeart.jpg

- File:1873 Pierre Auguste Cot - Spring.jpg

Art by animals[edit]

- File:Untitled 2010 Kissu.jpg

- File:UnicornTapestry.jpg

- File:Congo chimpanzee painting-1.jpg

- File:Chimpanzee congo painting.jpg

- File:Elephant show in Chiang Mai P1110486.JPG

- File:Elephant show in Chiang Mai P1110487.JPG

- File:Elephant Art (2266723284).jpg

Animals making art in art[edit]

- File:Van Kessel, Ferdinand the Younger (follower) - Le singe peintre - 17th c.jpg

- File:Louvre-peinture-francaise-singe-peintre-p1020296.jpg and File:Monkey Funk You.jpg

Other[edit]

fire in art[edit]

- File:14 dreams smokeless fire.png

- File:26062010 FragmentierterBaum15.jpg

- File:3 Dimensional Apophysis Fractal Flame.jpg

- File:Brugger Salemer Klosterbrand.jpg

- File:Burgnaturewl1.png

- File:Burning angel (Jimmy Fell).JPG

- File:Burning angel 3 (Jimmy Fell).jpg

- File:Burning of Moscow 1812 - Bandana 01.jpg

- File:BurningFlame0.gif

- File:Collage Auge im All byLöser.jpg

- File:Collage Auge im Feuer byLöser.jpg

- File:Daniel van Heil (attr) Brennende Stadt.jpg

- File:Death and Fire.JPG

- File:Derkovits, Gyula - Dózsa-series VIII. Stakes (1928).jpg

- File:Flying Skeleton Hell.gif

- File:Leopold Munsch Brand des Treumann-Theater.jpg

- File:Luginbuehl signal.jpg

External links[edit]

- Arturo Espinosa Rosique

- His work appears to all be released under Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic licenses

References[edit]

- ↑ Tchaikovsky Research : The Year 1812, Op. 49 (TH 49). Archived from the original on November 6, 2013. Retrieved on September 3, 2009.

- ↑ Lax, Roger (1989) The Great Song Thesaurus, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 230 ISBN: 978-0-19-505408-8.

- ↑ Felsenfeld, Daniel. Tchaikovsky: A Listener's Guide, p. 54 (Amadeus Press, 2006).

- ↑ Matz, Carol (2006) A Night at the Symphony, Category:New York: Alfred Publishing, p. 45 ISBN: 978-0-7390-4107-9.

- ↑ a b c d Whitmore, Janet (Ph.D.). Jules-Joseph Lefebvre (1836 - 1911). Rehs Galleries, Inc.. Retrieved on 2014-02-28.

- ↑ Words Latin-English Dictionary;Perseus Word Lookup

- ↑ James Hall, Dictionary of Subjects & Symbols in Art (New York: Harper & Row, 1974), 318.

- ↑ Edwin Mullins, The Painted Witch: How Western Artists Have Viewed the Sexuality of Women (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 1985), 62–3.

- ↑ http://essentialvermeer.20m.com/cat_about/necklace.htm

- ↑ "Man who defied tanks may be dead", Los Angeles Times, (3 June 1990).

Robin Munro and Mickey Spiegel, Detained in China and Tibet: a directory of political and religious prisoners (Asia Watch Committee, 1994), p. 194. ISBN 978-1-56432-105-3. - ↑ a b c The Unknown Rebel Time profile. Retrieved January 10, 2006.

- ↑ Langely, Andrew (2009) Tiananmen Square: Massacre Crushes China's Democracy Movement, Compass Point Books, pp. 45 ISBN: 978-0-7565-4101-9.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Witty, Patrick. Behind the Scenes: Tank Man of Tiananmen. The New York Times LENS Blog. Retrieved on 2014-03-01.

- ↑ Floor Speech on Tiananmen Square Resolution. Nancy Pelosi, Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives. June 3, 2009.

- ↑ Corless, Kieron (May 24, 2006). "Time In – Plugged In – Tank Man". Time Out. Retrieved on June 4, 2012.

- ↑ Witty, Patrick. Behind the Scenes: A New Angle on History. The New York Times LENS Blog. Retrieved on 2014-03-01.

- ↑ Alfano, Sean (June 4, 2009). ""Tank Man": The Picture That Almost Wasn't". Error: journal= not stated. CBS News.

- ↑ a b c Arthur Tsang Hin Wah interview, March 20, 2013

- ↑ Pictures I Like: Tankman, Charlie Cole, 1989. The Shrine of Dreams (2012-06-20). Retrieved on 2014-03-01.

- ↑ 1989, Charlie Cole, World Press Photo of the Year, World Press Photo of the Year, World Press Photo.

- ↑ Jones, Terril (2009). "Tank Man". Pomona College Magazine 41 (1).

- ↑ Picture Power: Tiananmen Standoff. BBC News. October 7, 2005.

- ↑ Legacy of June Fourth.

- ↑ a b Macartney, Jane (2009-05-30). "Identity of Tank Man of Tiananmen Square remains a mystery". The Times.

- ↑ The Tank Man: Interview: Jan Wong. Frontline. PBS (2006-04-11). Retrieved on 2014-03-01.

- ↑ Bisson, Terry (4 1991). "They're Made Out of Meat". OMNI.

- ↑ Bisson, Terry. They're Made out of Meat. Terry Bisson SF Story Showcase. Retrieved on 2009-12-10.

- ↑ Peak, Alexander S.. Fiction. alexpeak.com. Retrieved on 2014-02-28.

![By Sem[?]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f5/Liberty3869.jpg/72px-Liberty3869.jpg)

![Capricho No. 43: El sueño de la razón produce monstruos (The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, c. 1799) by Francisco de Goya. The full epigraph from the Prado etching version reads: "Fantasy abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters; united with her, she is the mother of the arts and the origin of their marvels."[1] Etching, aquatint, drypoint, and burin. Museo del Prado, Madrid.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f5/Museo_del_Prado_-_Goya_-_Caprichos_-_No._43_-_El_sue%C3%B1o_de_la_razon_produce_monstruos.jpg/81px-Museo_del_Prado_-_Goya_-_Caprichos_-_No._43_-_El_sue%C3%B1o_de_la_razon_produce_monstruos.jpg)

![The Muir portrait of Adam Smith (circa 1800). Oil on canvas, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh. The Muir portrait of Adam Smith is “so called after those who are known to have owned it. … We have no absolute confirmation, no positive actual proof, that the picture is of Adam Smith. We have definitive evidence that one such portrait of him existed. Beyond this, the most we should say is that the Muir portrait makes out quite the best claim to being an authentic portrait of Adam Smith [as] no other claimant has appeared with a comparable case” (A. L. Macfie, 1952).](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/43/Adam_Smith_The_Muir_portrait.jpg/98px-Adam_Smith_The_Muir_portrait.jpg)